John von Neumann

226 results back to index

Turing's Cathedral by George Dyson

1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy, Abraham Wald, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, Benoit Mandelbrot, Bletchley Park, British Empire, Brownian motion, cellular automata, Charles Babbage, cloud computing, computer age, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Danny Hillis, dark matter, double helix, Dr. Strangelove, fault tolerance, Fellow of the Royal Society, finite state, Ford Model T, Georg Cantor, Henri Poincaré, Herman Kahn, housing crisis, IFF: identification friend or foe, indoor plumbing, Isaac Newton, Jacquard loom, John von Neumann, machine readable, mandelbrot fractal, Menlo Park, Murray Gell-Mann, Neal Stephenson, Norbert Wiener, Norman Macrae, packet switching, pattern recognition, Paul Erdős, Paul Samuelson, phenotype, planetary scale, RAND corporation, random walk, Richard Feynman, SETI@home, social graph, speech recognition, The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen, Thorstein Veblen, Turing complete, Turing machine, Von Neumann architecture

Mariette von Neumann to John von Neumann, September 22, 1937, in Frank Tibor, “Double Divorce: The Case of Mariette and John von Neumann,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 34, no. 2 (1991): 361. 12. Mariette von Neumann to John von Neumann, n.d., 1937, in ibid. 13. Klára von Neumann to John von Neumann, November 11, 1937, KVN. 14. John von Neumann to Stanislaw Ulam, April 22, 1938, SFU. 15. Klára von Neumann, Two New Worlds. 16. John von Neumann to Klára von Neumann, September 14, 1938, KVN. 17. John von Neumann to Klára von Neumann, September 6, 1938, KVN. 18. John von Neumann to Klára von Neumann, September 5, 1938, KVN; John von Neumann to Klára von Neumann, September 13, 1938, KVN. 19.

…

Nicholas Vonneumann, interview with author. 10. Vonneumann, John von Neumann as Seen by His Brother, pp. 23, 16. 11. Ibid., p. 24. 12. Nicholas Vonneumann, interview with author. 13. Stanislaw Ulam, “John von Neumann: 1903–1957,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 64, no. 3, part 2 (May 1958): 1. 14. Klára von Neumann, Johnny, ca. 1963, KVN; Ulam, “John von Neumann: 1903–1957,” 2:37. 15. John von Neumann to Stan Ulam, December 9, 1939, SFU; Oskar Morgenstern, in John von Neumann, documentary produced by the Mathematical Association of America, 1966. 16. Klára von Neumann, Johnny. 17. John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1944), p. 2; Samuelson, “A Revisionist View of Von Neumann’s Growth Model,” in M.

…

Jack Rosenberg, interview with author, February 12, 2005; Marina von Neumann Whitman, interview with author, February 9, 2006. 29. Klára von Neumann to John von Neumann, n.d., ca. 1949, KVN. 30. Klára von Neumann, Johnny. 31. Ibid. 32. John von Neumann and Oswald Veblen to Frank Aydelotte, March 23, 1940, IAS. 33. Ibid. 34. Klára von Neumann, Johnny. 35. John von Neumann to Stanislaw Ulam, April 2, 1942, VNLC; John von Neumann to Clara [Klára] von Neumann, April 13, 1943, KVN; S. W. Hubbel [Office of Censorship] to Clara [Klára] von Neumann, April 13, 1943, IAS. 36. Klára von Neumann, Johnny. 37. John von Neumann to Klára von Neumann, May 8, 1945, KVN; John von Neumann to Klára von Neumann, May 11, 1945, KVN. 38.

pages: 476 words: 121,460

The Man From the Future: The Visionary Life of John Von Neumann by Ananyo Bhattacharya

Ada Lovelace, AI winter, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, Alvin Roth, Andrew Wiles, Benoit Mandelbrot, business cycle, cellular automata, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, clockwork universe, cloud computing, Conway's Game of Life, cuban missile crisis, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, DeepMind, deferred acceptance, double helix, Douglas Hofstadter, Dr. Strangelove, From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death, Georg Cantor, Greta Thunberg, Gödel, Escher, Bach, haute cuisine, Herman Kahn, indoor plumbing, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Isaac Newton, Jacquard loom, Jean Tirole, John Conway, John Nash: game theory, John von Neumann, Kenneth Arrow, Kickstarter, linear programming, mandelbrot fractal, meta-analysis, mutually assured destruction, Nash equilibrium, Norbert Wiener, Norman Macrae, P = NP, Paul Samuelson, quantum entanglement, RAND corporation, Ray Kurzweil, Richard Feynman, Ronald Reagan, Schrödinger's Cat, second-price auction, side project, Silicon Valley, spectrum auction, Steven Levy, Strategic Defense Initiative, technological singularity, Turing machine, Von Neumann architecture, zero-sum game

Fellner would initially study the subject for similar reasons. All three would drop it quite soon after finishing their degrees to pursue their true passions. 23. Quoted in Stanisław Ulam, ‘John von Neumann 1903–1957’, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 64 (1958), pp. 1–49. 24. John von Neumann, ‘Eine Axiomatisierung der Mengenlehre’, Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, 154 (1925), pp. 219–40. 25. John von Neumann, ‘Die Axiomatisierung der Mengenlehre’, Mathematische Zeitschrift, 27 (1928), pp. 669–752. 26. Quoted in Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral. CHAPTER 3: THE QUANTUM EVANGELIST 1.

…

Quoted in Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral. 18. https://libertyellisfoundation.org/passenger-details/czoxMzoiOTAxMTk4OTg3MDU0MSI7/czo4OiJtYW5pZmVzdCI7. 19. Details of Meitner’s life drawn from Ruth Lewin Sime, 1996, Lise Meitner: A Life in Physics, University of California Press, Berkeley. 20. John von Neumann, 2005, John von Neumann: Selected Letters, ed. Miklós Rédei, American Mathematical Society, Providence, R.I. 21. Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar and John von Neumann, 1942, ‘The Statistics of the Gravitational Field Arising from a Random Distribution of Stars. I. The Speed of Fluctuations’, Astrophysical Journal, 95 (1942), pp. 489–531. 22. Thomas Haigh and Mark Priestly have recently made the case that von Neumann was not much influenced by Turing when it came to computer design, based on the text of three lectures they discovered: ‘Von Neumann Thought Turing’s Universal Machine Was “Simple and Neat”.

…

., and William Aspray, 1990, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2. A slightly longer excerpt is quoted in Leonard, Von Neumann, Morgenstern, and the Creation of Game Theory Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 3. See Macrae, John von Neumann. 4. Earl of Halsbury, ‘Ten Years of Computer Development’, Computer Journal, 1 (1959), pp. 153–9. 5. Brian Randell, 1972, On Alan Turing and the Origins of Digital Computers, University of Newcastle upon Tyne Computing Laboratory, Technical report series. 6. Quoted in Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing. 7.

pages: 463 words: 118,936

Darwin Among the Machines by George Dyson

Ada Lovelace, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, backpropagation, Bletchley Park, British Empire, carbon-based life, cellular automata, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, combinatorial explosion, computer age, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Danny Hillis, Donald Davies, fault tolerance, Fellow of the Royal Society, finite state, IFF: identification friend or foe, independent contractor, invention of the telescope, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, Jacquard loom, James Watt: steam engine, John Nash: game theory, John von Neumann, launch on warning, low earth orbit, machine readable, Menlo Park, Nash equilibrium, Norbert Wiener, On the Economy of Machinery and Manufactures, packet switching, pattern recognition, phenotype, RAND corporation, Richard Feynman, spectrum auction, strong AI, synthetic biology, the scientific method, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Turing machine, Von Neumann architecture, zero-sum game

Berkeley, Giant Brains (New York: John Wiley, 1949), 5. 45.John von Neumann, 1948, “The General and Logical Theory of Automata,” in Lloyd A. Jeffress, ed., Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior: The Hixon Symposium (New York: Hafner, 1951), 31. 46.Stanislaw Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician (New York: Scribner’s, 1976), 242. 47.John von Neumann, 1948, response to W. S. McCulloch’s paper “Why the Mind Is in the Head,” Hixon Symposium, September 1948, in Jeffress, Cerebral Mechanisms, 109–111. 48.John von Neumann to Oswald Veblen, memorandum, 26 March 1945, “On the Use of Variational Methods in Hydrodynamics,” reprinted in John von Neumann, Theory of Games, Astrophysics, Hydrodynamics and Meteorology, vol. 6 of Collected Works, ed.

…

Dyson, Disturbing the Universe (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 194. 2.Stanislaw Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician (New York: Scribner’s, 1976), 231. 3.Nicholas Vonneumann, “John von Neumann: Formative Years,” Annals of the History of Computing 11, no. 3 (1989): 172. 4.Eugene P. Wigner, “John von Neumann—A Case Study of Scientific Creativity,” Annals of the History of Computing. 11, no. 3 (1989): 168. 5.Edward Teller, in Jean R. Brink and Roland Haden, “Interviews with Edward Teller and Eugene P. Wigner,” Annals of the History of Computing 11, no. 3 (1989): 177. 6.Stanislaw Ulam, “John von Neumann, 1903–1957,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 64, no. 3 (May 1958): 1. 7.Eugene Wigner, “Two Kinds of Reality,” The Monnist 49, no. 2 (April 1964); reprinted in Symmetries and Reflections (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1967), 198. 8.John von Neumann, statement on nomination to membership in the AEC, 8 March 1955, von Neumann Papers, Library of Congress; in William Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 247. 9.John von Neumann, as quoted by J.

…

Wigner,” Annals of the History of Computing 11, no. 3 (1989): 177. 6.Stanislaw Ulam, “John von Neumann, 1903–1957,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 64, no. 3 (May 1958): 1. 7.Eugene Wigner, “Two Kinds of Reality,” The Monnist 49, no. 2 (April 1964); reprinted in Symmetries and Reflections (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1967), 198. 8.John von Neumann, statement on nomination to membership in the AEC, 8 March 1955, von Neumann Papers, Library of Congress; in William Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 247. 9.John von Neumann, as quoted by J. Robert Oppenheimer in testimony before the AEC Personnel Security Board, 16 April 1954, In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1954; reprint, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1970), 246 (page citation is to the reprint edition). 10.Nicholas Metropolis, “The MANIAC,” in Nicholas Metropolis, J.

pages: 323 words: 100,772

Prisoner's Dilemma: John Von Neumann, Game Theory, and the Puzzle of the Bomb by William Poundstone

90 percent rule, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, cuban missile crisis, Douglas Hofstadter, Dr. Strangelove, Frank Gehry, From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death, Herman Kahn, Jacquard loom, John Nash: game theory, John von Neumann, Kenneth Arrow, means of production, Monroe Doctrine, mutually assured destruction, Nash equilibrium, Norbert Wiener, RAND corporation, Richard Feynman, seminal paper, statistical model, the market place, zero-sum game

The Anchor Books edition is published by arrangement with Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc. Anchor Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. The quotes from letters of John von Neumann on pp. 22, 65, 75, 140–41, and 180 are from materials in the John von Neumann archives, Library of Congress, and are used with permission of Marina von Neumann Whitman. The excerpts from “The Mathematician” by John von Neumann on pp. 28–29 are used with permission of the University of Chicago Press. Copyright © 1950. The quotations from letters of J. D. Williams on pp. 94–95 are used with permission of Evelyn Williams Snow.

…

Thanks for recollections, assistance, or advice must also go to Paul Armer, Robert Axelrod, Sally Beddow, Raoul Bott, George B. Dantzig, Paul Halmos, Jeane Holiday, Cuthbert Hurd, Martin Shubik, John Tchalenko, Edward Teller, and Nicholas A. Vonneuman. CONTENTS Cover Other Books by this Author Title Page Dedication Acknowledgments 1 DILEMMAS The Nuclear Dilemma John von Neumann Prisoner’s Dilemma 2 JOHN VON NEUMANN The Child Prodigy Kun’s Hungary Early Career The Institute Klara Personality The Sturm und Drang Period The Best Brain in the World 3 GAME THEORY Kriegspiel Who Was First? Theory of Games and Economic Behavior Cake Division Rational Players Games as Trees Games as Tables Zero-Sum Games Minimax and Cake Mixed Strategies Curve Balls and Deadly Genes The Minimax Theorem N-Person Games 4 THE BOMB Von Neumann at Los Alamos Game Theory in Wartime Bertrand Russell World Government Operation Crossroads The Computer Preventive War 5 THE RAND CORPORATION History Thinking About the Unthinkable Surfing, Semantics, Finnish Phonology Von Neumann at RAND John Nash The Monday-Morning Quarterback 6 PRISONER’S DILEMMA The Buick Sale Honor Among Thieves The Flood-Dresher Experiment Tucker’s Anecdote Common Sense Prisoner’s Dilemmas in Literature Free Rider Nuclear Rivalry 7 1950 The Soviet Bomb The Man from Mars Urey’s Speech The Fuchs Affair The Korean War The Nature of Technical Surprise Aggressors for Peace Francis Matthews Aftermath Public Reaction Was It a Trial Balloon?

…

Today, with East-West tensions relaxing, preventive war seems a curious aberration of cold-war mentality. Yet the same sorts of issues are very much with us today. What should a nation do when its security conflicts with the good of all humanity? What should a person do when his or her interests conflict with the common good? JOHN VON NEUMANN Perhaps no one exemplifies the agonizing dilemma of the bomb better than John von Neumann (1903–1957). That name does not mean much to most people. The celebrity mathematician is almost a nonexistent species. Those few laypersons who recognize the name are most likely to place him as a pioneer of the electronic digital computer, or as one of the crowd of scientific luminaries who worked on the Manhattan Project.

pages: 253 words: 80,074

The Man Who Invented the Computer by Jane Smiley

1919 Motor Transport Corps convoy, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, Arthur Eddington, Bletchley Park, British Empire, c2.com, Charles Babbage, computer age, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, Fellow of the Royal Society, Ford Model T, Henri Poincaré, IBM and the Holocaust, Isaac Newton, John von Neumann, Karl Jansky, machine translation, Norbert Wiener, Norman Macrae, Pierre-Simon Laplace, punch-card reader, RAND corporation, Turing machine, Vannevar Bush, Von Neumann architecture

Presper Eckert, only eighteen, was applying to college at MIT, though in the end he went to business school at the University of Pennsylvania. Konrad Zuse, in Berlin, had already built one computer (the Z1) in his parents’ apartment. He later said that if the building had not been bombed, he would not have been able to get his machine out of the apartment. John von Neumann, born in Hungary but living in Princeton, New Jersey, had become so convinced that war in Europe was inevitable that he had applied for U.S. citizenship. He received his naturalization papers in December 1937. Von Neumann was one of the most talented mathematicians of his day, but he wasn’t yet involved with computers.

…

In some ways, Alan Turing was Atanasoff’s precise opposite, drawn to pure mathematics rather than practical physics, educated to think rather than to tinker, disorganized in his approach rather than systematic, never a family man and required by his affections and his war work to be utterly secretive. His figure is now so mysterious and tragically evocative that he has become the most famous of our inventors. The man who was best known in his own lifetime, John von Neumann, has retreated into history, more associated with the atomic bomb and the memory of the cold war than with the history of the computer, but it was von Neumann who made himself the architect of that history without, in some sense, ever lifting a screwdriver (in fact, his wife said that he was not really capable of lifting a screwdriver).

…

If, at the University of Florida and Iowa State, and even at the University of Wisconsin, Atanasoff was always more or less at the periphery of both the mathematics and physics establishments, at King’s College Turing was at the exact heart, especially of mathematics. He took courses from astrophysicist Arthur Eddington and mathematicians G. H. Hardy and Max Born. He met John von Neumann there—many mathematicians fleeing conditions in Germany and the East passed through Cambridge on their way to settling elsewhere. And it was Max Newman, who was lecturing on topology—the study of relationships between geometric spaces as they are transformed by such operations as stretching, but not such operations as cutting—who introduced him to the Hilbert problem that would make his career.

pages: 998 words: 211,235

A Beautiful Mind by Sylvia Nasar

Al Roth, Albert Einstein, Andrew Wiles, Bletchley Park, book value, Brownian motion, business cycle, cognitive dissonance, Columbine, Dr. Strangelove, experimental economics, fear of failure, Gunnar Myrdal, Henri Poincaré, Herman Kahn, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, John Conway, John Nash: game theory, John von Neumann, Kenneth Arrow, Kenneth Rogoff, linear programming, lone genius, longitudinal study, market design, medical residency, Nash equilibrium, Norbert Wiener, Paul Erdős, Paul Samuelson, prisoner's dilemma, RAND corporation, Robert Solow, Ronald Coase, second-price auction, seminal paper, Silicon Valley, Simon Singh, spectrum auction, Suez canal 1869, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thorstein Veblen, upwardly mobile, zero-sum game

Kuhn, interview. 27. Ibid. 28. Milnor, interview, 9.26.95. 7: John von Neumann 1. See, for example, Stanislaw Ulam, “John von Neumann, 1903–1957,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 64, no. 3, part 2 (May 1958); Stanislaw Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician (New York: Scribner’s, 1983); Paul R. Halmos, “The Legend of John von Neumann,” American Mathematical Monthly, vol. 80 (1973); William Poundstone, Prisoner’s Dilemma, op. cit.; Ed Regis, Who Got Einstein’s Office?, op. cit. 2. Poundstone, op. cit. 3. Ulam, “John von Neumann,” op. cit.; Poundstone, op. cit., pp. 94–96. 4. Harold Kuhn, interview, 1.10.96. 5.

…

Nash shared von Neumann’s interest in game theory, quantum mechanics, real algebraic variables, hydrodynamic turbulence, and computer architecture. 6. See, for example, Ulam, “John von Neumann,” op. cit. 7. Norman McRae, John von Neumann (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), pp. 350–56. 8. John von Neumann, The Computer and the Brain (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959). 9. See, for example, G. H. Hardy, A Mathematician’s Apology (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1967), with a foreword by C. P. Snow. 10. Ulam, “John von Neumann,” op. cit. 11. Poundstone, op. cit. 12. Poundstone, Prisoner’s Dilemma, p. 190. 13. Clay Blair, Jr., “Passing of a Great Mind,” Life (February 1957), pp. 89–90, as quoted by Poundstone, op. cit., p. 143. 14.

…

., “Passing of a Great Mind,” Life (February 1957), pp. 89–90, as quoted by Poundstone, op. cit., p. 143. 14. Poundstone, op. cit. 15. Ulam, “John von Neumann,” op. cit. 16. Harold Kuhn, interview, 3.97. 17. Paul R. Halmos, “The Legend of John von Neumann,” op. cit. 18. Ibid. 19. Poundstone, op. cit. 20. Halmos, op. cit. 21. Ibid. 22. Poundstone, op. cit. 23. Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician, op. cit. 24. Ulam, “John von Neumann,” op. cit. 25. Ibid. 26. Ibid., p. 10; Robert J. Leonard, “From Parlor Games to Social Science,” op. cit. 27. Richard Duffin, interview, 10.94. 28. Halmos, op. cit. 29. Ulam, “John von Neumann,” op. cit., pp. 35–39. 30. Interviews with Donald Spencer, 11.18.95; David Gale, 9.20.95; and Harold Kuhn, 9.23.95. 31.

pages: 377 words: 97,144

Singularity Rising: Surviving and Thriving in a Smarter, Richer, and More Dangerous World by James D. Miller

23andMe, affirmative action, Albert Einstein, artificial general intelligence, Asperger Syndrome, barriers to entry, brain emulation, cloud computing, cognitive bias, correlation does not imply causation, crowdsourcing, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, David Brooks, David Ricardo: comparative advantage, Deng Xiaoping, en.wikipedia.org, feminist movement, Flynn Effect, friendly AI, hive mind, impulse control, indoor plumbing, invention of agriculture, Isaac Newton, John Gilmore, John von Neumann, knowledge worker, Larry Ellison, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, low skilled workers, Netflix Prize, neurotypical, Nick Bostrom, Norman Macrae, pattern recognition, Peter Thiel, phenotype, placebo effect, prisoner's dilemma, profit maximization, Ray Kurzweil, recommendation engine, reversible computing, Richard Feynman, Rodney Brooks, Silicon Valley, Singularitarianism, Skype, statistical model, Stephen Hawking, Steve Jobs, sugar pill, supervolcano, tech billionaire, technological singularity, The Coming Technological Singularity, the scientific method, Thomas Malthus, transaction costs, Turing test, twin studies, Vernor Vinge, Von Neumann architecture

Von Neumann made Stalin unwilling to risk war because von Neumann shaped U.S. weapons policy—in part by pushing the United States to develop hydrogen bombs—to let Stalin know that the only human life Stalin actually valued would almost certainly perish in World War III. 20 Johnny helped develop a superweapon, played a key role in integrating it into his nation’s military, advocated that it be used, and then made sure that his nation’s enemies knew that in a nuclear war they would be personally struck by this superweapon. John von Neumann could himself reasonably be considered the most powerful weapon ever to rest on American soil. Now consider the strategic implications if the Chinese high-tech sector and military acquired a million computers with the brilliance of John von Neumann, or if, through genetic manipulation, they produced a few thousand von Neumann-ish minds every year. Contemplate the magnitude of the resources the US military would pour into artificial intelligence if it thought that a multitude of digital or biological von Neumanns would someday power the Chinese economy and military.

…

But whole brain emulation is still a path to the Singularity that could work, even if a Kurzweilian merger proves beyond the capacity of bioengineers. If we had whole brain emulations, Moore’s Law would eventually give us some kind of Singularity. Imagine we just simulated the brain of John von Neumann. If the (software adjusted) speed of computers doubled every year, then in twenty years we could run this software on computers that were a million times faster and in forty years on computers that were a trillion times faster. The innovations that a trillion John von Neumanns could discover in one year would change the world beyond our current ability to imagine. 3.Clues from the Brain Even if we never figure out how to emulate our brains or merge them with machines, clues to how our brains work could help scientists figure out how to create other kinds of human-level artificial intelligence.

…

If the following diagram is right, we would likely have a lot of warning time between when AIs reach chimp level and when they become ultra-intelligent. But this first diagram might overstate differences in intelligence. The basic structure of my brain is pretty close to that of chimps and shockingly similar to John von Neumann’s. Perhaps, under some grand theory of intelligence, once you’ve reached chimp level it doesn’t take all that many more tweaks to go well past John von Neumann. If this next diagram has the relative sizes of intelligences right, then it might take very little time for an AI to achieve superintelligence once it becomes as smart as a chimp. As I’ll discuss in Chapter 7, there are a huge number of genes, each of which slightly contributes to a person’s intelligence.

pages: 558 words: 164,627

The Pentagon's Brain: An Uncensored History of DARPA, America's Top-Secret Military Research Agency by Annie Jacobsen

Albert Einstein, Berlin Wall, Boston Dynamics, colonial rule, crowdsourcing, cuban missile crisis, Dean Kamen, disinformation, Dr. Strangelove, drone strike, Edward Snowden, Fall of the Berlin Wall, game design, GPS: selective availability, Herman Kahn, Ivan Sutherland, John Markoff, John von Neumann, license plate recognition, Livingstone, I presume, low earth orbit, megacity, Menlo Park, meta-analysis, Mikhail Gorbachev, military-industrial complex, Murray Gell-Mann, mutually assured destruction, Neil Armstrong, Norman Mailer, operation paperclip, place-making, RAND corporation, restrictive zoning, Ronald Reagan, Ronald Reagan: Tear down this wall, social intelligence, stem cell, Stephen Hawking, Strategic Defense Initiative, traumatic brain injury, zero-sum game

The computer designed by John von Neumann played an important role in allowing Livermore scientists to model new nuclear weapons designs before building them. In the summer of 1955, John von Neumann was diagnosed with cancer. He had slipped and fallen, and when doctors examined him, they discovered that he had an advanced, metastasizing cancerous tumor in his collarbone. By November his spine was affected, and in January 1956 von Neumann was confined to a wheelchair. In March he entered a guarded room at Walter Reed Hospital, the U.S. Army’s flagship medical center, outside Washington, D.C. John von Neumann, at the age of fifty-four, racked with pain and riddled with terror, was dying of a cancer he most likely developed because of a speck of plutonium he inhaled at Los Alamos during the war.

…

Air Force brawn: Abella, photographs, (unpaginated). 2 game pieces scattered: Leonard, 339. 3 “credibility”: York, Making Weapons, 89. 4 remarkable child prodigy: S. Bochner, John Von Neumann, 1903–1957, National Academy of Sciences, 442–450. 5 “unsolved problem”: P. R. Halmos, “The Legend of John Von Neumann,” Mathematical Association of America, Vol. 80, No. 4, April 1973, 386. 6 “He was pleasant”: York, Making Weapons, 89. 7 “I think”: Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon, 63. 8 “all-out atomic war”: Whitman, 52. 9 maximum kill rate: “Citation to Accompany the Award of the Medal of Merit to Dr. John von Neumann,” October 1946, Von Neumann Papers, LOC. 10 “a mentally superhuman race”: Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral, 45. 11 Prisoner’s Dilemma: Poundstone, 8-9, 103-106. 12 something unexpected: Abella, 55–56; Poundstone, 121-123. 13 “How can you persuade”: McCullough, 758. 14 Goldstine explained: Information on Goldstine comes from Jon Edwards, “A History of Early Computing at Princeton,” Princeton Alumni Weekly, August 27, 2012. 15 von Neumann declared: Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral, 73. 16 “Our universe”: George Dyson, “‘An Artificially Created Universe’: The Electronic Computer Project at IAS,” Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton (Spring 2012), 8-9. 17 secured funding: Maynard, “Daybreak of the Digital Age,” Princeton Alumni Weekly, April 4, 2012. 18 he erred: Jon Edwards, “A History of Early Computing at Princeton,” Princeton Alumni Weekly, August 27, 2012, 4. 19 Wohlstetter’s famous theory: Wohlstetter, “The Delicate Balance of Terror,” 1-12. 20 Debris: Descriptions of shock wave and blast effects are described in Garrison, 23-29. 21 Georg Rickhey: Information on Rickhey comes from Bundesarchiv Ludwigsburg and RG 330 JIOA Foreign Scientist Case Files, NACP.

…

Competition was valued and encouraged at RAND, with scientists and analysts always working to outdo one another. Lunchtime war games included at least one person in the role of umpire, which usually prevented competitions from getting out of hand. Still, tempers flared, and sometimes game pieces scattered. Other times there was calculated calm. Lunch could last for hours, especially if John von Neumann was in town. In the 1950s, von Neumann was the superstar defense scientist. No one could compete with his brain. At the Pentagon, the highest-ranking members of the U.S. armed services, the secretary of defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, all saw von Neumann as an infallible authority. “If anyone during that crucial period in the early and middle-fifties can be said to have enjoyed more ‘credibility’ in national defense circles than all the others, that person was surely Johnny,” said Herb York, von Neumann’s close friend.

pages: 406 words: 108,266

Journey to the Edge of Reason: The Life of Kurt Gödel by Stephen Budiansky

Abraham Wald, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, business cycle, Douglas Hofstadter, fear of failure, Fellow of the Royal Society, four colour theorem, Georg Cantor, Gregor Mendel, Gödel, Escher, Bach, John von Neumann, laissez-faire capitalism, P = NP, P vs NP, Paul Erdős, rent control, scientific worldview, the scientific method, Thorstein Veblen, Turing machine, urban planning

., Notizbücher, 376, 390. 20.Enzensberger, “Hommage à Gödel,” reprinted in W&B, 25 (my translation). 21.KG, “Existence of Undecidable Propositions,” 6. 22.KG, “Existence of Undecidable Propositions,” 6–7. 23.KG, “Situation in Foundations of Mathematics,” CW, 3:50–51. 24.KG, “Existence of Undecidable Propositions,” 8–9. 25.KG, “Undecidable Propositions of Formal Systems,” CW, 1:355. 26.KG, “Existence of Undecidable Propositions,” 14. 27.KG, “Undecidable Propositions of Formal Systems,” CW, 1:359. 28.Kleene, “Kurt Gödel,” 154. 29.Vinnikov, “Hilbert’s Apology.” 30.Heinrich Scholz to Rudolf Carnap, 16 April 1931, quoted in Mancosu, “Reception of Gödel’s Theorem,” 33; Marcel Natkin to KG, 27 June 1931, KGP, 2c/114. 31.Goldstine, Pascal to von Neumann, 167–68. 32.John von Neumann to KG, 20 November 1930, CW, 5:336–39. 33.Drafts of KG to John von Neumann, late November 1930, quoted in von Plato, “Sources of Incompleteness,” 4050–51. 34.John von Neumann to KG, 29 November 1930, CW, 5:338. 35.Von Plato, “Sources of Incompleteness,” 4054. 36.Ulam, Adventures of a Mathematician, 80; Goldstine, Pascal to von Neumann, 174. 37.Statement in Connection with the First Presentation of the Albert Einstein Award to Dr.

…

., 1938], Veblen, Papers, 8/10; Karl Menger to KG, [December 1938], CW, 5:125. 53.KG to Karl Menger, 25 June, 19 October, and 11 November 1938, quoted in Menger, Reminiscences, 218–19. 54.Menger, Reminiscences, 220–21. 55.Menger, Reminiscences, 224. 56.Menger, Reminiscences, 224–25; KG to Karl Menger, 30 August 1939, CW, 5:124–26; OMD, 19 March 1972. 57.KG to Oswald Veblen, draft letter, November 1939, KGP, 13c/197. 58.John von Neumann to Abraham Flexner, 27 September 1939, quoted in Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral, 96; von Neumann to KG, telegram, 5 October 1939, IAS, Faculty Files, Pre-1953. 59.John von Neumann to Abraham Flexner, 16 October 1939, IAS, Visa-Immigration. 60.Ash, “Universität Wien,” 124–25; Friedrich Plattner to Rektor der Universität, 12 August 1939, reproduced in GA, 67–68. 61.Arthur Marchet to Rektor der Universität, 30 September 1939, reproduced in GA, 72. 62.Dawson, Logical Dilemmas, 140; KG to Devisenstelle Wien, 29 July 1939, reproduced in GA, 65–66. 63.KG to Oswald Veblen, draft letter, November 1939, KGP, 3c/197; Menger, Reminiscences, 224; Kreisel, “Kurt Gödel,” 155. 64.Frank Aydelotte to Chargé d’Affaires, German Embassy, 1 December 1939, IAS, Faculty Files, Pre-1953. 65.Der Dekan to Rektor der Universität, 27 November 1939, reproduced in GA, 71. 66.KG to Frank Aydelotte, 5 January 1940, IAS, Faculty Files, Pre-1953; KG to Institute for Advanced Study, telegram, 15 January 1940, ibid.; KG passport, KGP, 13a/8. 67.KG to MG, 29 November 1965 (“I still recall the suitcase of things that Adele brought back from there in 1940”). 68.KG to RG, 31 March 1940; KG to Institute for Advanced Study, telegram, 5 March 1940, IAS, Faculty Files, Pre-1953. 69.OMD, 10 March 1940.

…

Philip Erlich Walking with Einstein Railroad line to Brünn, 1838 Brünn’s city theater Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, 1906 (map) Vienna’s medieval glacis The Ringstraße, nearing completion Vienna’s prototype anti-Semite, Karl Lueger Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein by Gustav Klimt, 1905 Self-portrait of Ernst Mach Brünn’s textile mills, 1915 Brünn (map) Gödel as a baby The Gödel family Gödel Villa in Brünn Realgymnasium, Brünn Gödel’s school report card Gödel’s Vienna (map) Café Arkaden Albert Einstein in Vienna, 1921 University of Vienna Olga Taussky Philipp Furtwängler Gödel as a student Hans Hahn Anti-Semitic attacks at the university The Bärenhöhle Justizpalast attack, 1927 Moritz Schlick Café Josephinum Karl Menger Rudolf Carnap Ludwig Wittgenstein At tea with Olga Taussky and foreign visitors With Adele in Vienna Adele on stage, age nineteen Marked-up proof page of the Incompleteness Theorem Gödel’s lecture fees, 1937 Hiking near the Rax Josefstädter Straße Oswald Veblen Princeton, 1930s John von Neumann Nazi students and faculty at the University of Vienna, 1931 With Alfred Tarski, 1935 Purkersdorf Sanatorium Receipt for stay at Purkersdorf Rekawinkel Sanatorium Portrait of Adele, 1932 Moritz Schlick’s murder Hans Nelböck on trial Gödel’s 1937–38 shorthand diary Grinzing, 1938 Nazi takeover at the University of Vienna, 1938 Adele’s NSDAP application Wedding portrait, September 1938 Passport and cables, 1940 Crossing the Pacific with Adele Fuld Hall Verena Huber-Dyson With Albert Einstein With Oskar Morgenstern Receiving the Einstein Award, 1951 With Adele at Linden Lane Working outdoors With the flamingo With Rudi and Marianne Gödel in Princeton Gödel’s office in the new library Student protests in Princeton, 1969 At the Institute for Advanced Study garden party, 1973 JOURNEY to the EDGE of REASON At the Institute for Advanced Study, 1956 PROLOGUE MARCH 1970.

pages: 524 words: 120,182

Complexity: A Guided Tour by Melanie Mitchell

Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, Albert Michelson, Alfred Russel Wallace, algorithmic management, anti-communist, Arthur Eddington, Benoit Mandelbrot, bioinformatics, cellular automata, Claude Shannon: information theory, clockwork universe, complexity theory, computer age, conceptual framework, Conway's Game of Life, dark matter, discrete time, double helix, Douglas Hofstadter, Eddington experiment, en.wikipedia.org, epigenetics, From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death, Garrett Hardin, Geoffrey West, Santa Fe Institute, Gregor Mendel, Gödel, Escher, Bach, Hacker News, Hans Moravec, Henri Poincaré, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, John Conway, John von Neumann, Long Term Capital Management, mandelbrot fractal, market bubble, Menlo Park, Murray Gell-Mann, Network effects, Norbert Wiener, Norman Macrae, Paul Erdős, peer-to-peer, phenotype, Pierre-Simon Laplace, power law, Ray Kurzweil, reversible computing, scientific worldview, stem cell, Stuart Kauffman, synthetic biology, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, Tragedy of the Commons, Turing machine

“When his mother once stared rather aimlessly”: Macrae, N., John von Neumann. New York: Pantheon, 1992, p. 52. “the greatest paper on mathematical economics”: Quoted in Macrae, N., John von Neumann. New York: Pantheon, 1992, p. 23. “the most important document ever written on computing and computers”: Goldstine, H. H., The Computer, from Pascal to von Neumann. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, first edition, 1972, p. 191. “Five of Hungary’s six Nobel Prize winners”: Macrae, N., John von Neumann. New York: Pantheon, 1992, p. 32. “The [IAS] School of Mathematics”: Quoted in Macrae, N., John von Neumann. New York: Pantheon, 1992, p. 324.

…

In fact, it is one of the simplest systems to capture the essence of chaos: sensitive dependence on initial conditions. The logistic map was brought to the attention of population biologists in a 1971 article by the mathematical biologist Robert May in the prestigious journal Nature. It had been previously analyzed in detail by several mathematicians, including Stanislaw Ulam, John von Neumann, Nicholas Metropolis, Paul Stein, and Myron Stein. But it really achieved fame in the 1980s when the physicist Mitchell Feigenbaum used it to demonstrate universal properties common to a very large class of chaotic systems. Because of its apparent simplicity and rich history, it is a perfect vehicle to introduce some of the major concepts of dynamical systems theory and chaos.

…

This simple-sounding problem turns out to have echos in the work of Kurt Gödel and Alan Turing, which I described in chapter 4. The solution also contains an essential means by which biological systems themselves get around the infinite regress. The solution was originally found, in the context of a more complicated problem, by the twentieth-century Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann. Von Neumann was a pioneer in fields ranging from quantum mechanics to economics and a designer of one of the earliest electronic computers. His design consisted of a central processing unit that communicates with a random access memory in which both programs and data can be stored. It remains the basic design of all standard computers today.

pages: 352 words: 120,202

Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology by Howard Rheingold

Ada Lovelace, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Bletchley Park, card file, cellular automata, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, combinatorial explosion, Compatible Time-Sharing System, computer age, Computer Lib, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, conceptual framework, Conway's Game of Life, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, experimental subject, Hacker Ethic, heat death of the universe, Howard Rheingold, human-factors engineering, interchangeable parts, invention of movable type, invention of the printing press, Ivan Sutherland, Jacquard loom, John von Neumann, knowledge worker, machine readable, Marshall McLuhan, Menlo Park, Neil Armstrong, Norbert Wiener, packet switching, pattern recognition, popular electronics, post-industrial society, Project Xanadu, RAND corporation, Robert Metcalfe, Silicon Valley, speech recognition, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Stewart Brand, Ted Nelson, telemarketer, The Home Computer Revolution, Turing machine, Turing test, Vannevar Bush, Von Neumann architecture

At the age of forty-two, he committed suicide, hounded cruelly by the same government he helped save. John von Neumann spoke five languages and knew dirty limericks in all of them. His colleagues, famous thinkers in their own right, all agreed that the operations of Johnny's mind were too deep and far too fast to be entirely human. He was one of history's most brilliant physicists, logicians, and mathematicians, as well as the software genius who invented the first electronic digital computer. John von Neumann was the center of the group who created the "stored program" concept that made truly powerful computers possible, and he specified a template that is still used to design almost all computers--the "von Neumann architecture."

…

Turing, "Computing Machinery and intelligence," Mind, vol. 59, no. 236 (1950). [7] Ibid. [8] Hodges, Turing, 488. Chapter Four: Johnny Builds Bombs and Johnny Builds Brains [1] Steve J. Heims, John von Neumann and Norbert Wiener (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1980), 371. [2] C. Blair, "Passing of a great Mind," Life,, February 25, 1957, 96. [3] Stanislaw Ulam, "John von Neumann, 1903-1957," Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 64, (1958), 4. [4] Goldstine, The Computer, 182. [5] Daniel Bell, The coming of Post-Industrial Society (New York: Basic Books. 1973), 31

…

They built a tic-tac-toe machine, but gave up on it as a moneymaking venture when an adviser assured them that P. T. Barnum's General Tom Thumb had sewn up the market for traveling novelties. Ironically, although Babbage's game-playing machines were commercial failures, his theoretical approach created a foundation for the future science of game theory, scooping even that twentieth-century genius John von Neumann by about a hundred years. It was Charley and Ada's attempt to develop an infallible system for betting on the ponies that brought Ada to the sorry pass of twice pawning her husband's family jewels, without his knowledge, to pay off blackmailing bookies. At one point, Ada and Babbage--never one to turn down a crazy scheme--used the existing small scale working model of the Difference Engine to perform the calculations required by their complex handicapping scheme.

The Fractalist by Benoit Mandelbrot

Albert Einstein, Benoit Mandelbrot, Brownian motion, business cycle, Claude Shannon: information theory, discrete time, double helix, financial engineering, Georg Cantor, Henri Poincaré, Honoré de Balzac, illegal immigration, Isaac Newton, iterative process, Johannes Kepler, John von Neumann, linear programming, Louis Bachelier, Louis Blériot, Louis Pasteur, machine translation, mandelbrot fractal, New Journalism, Norbert Wiener, Olbers’ paradox, Paul Lévy, power law, Richard Feynman, statistical model, urban renewal, Vilfredo Pareto

Am I describing a nightmare? No, but I wish I was. Having left MIT, I was spending the year 1953–54 at IAS as the last postdoctoral fellow that von Neumann sponsored. That lecture came about one day during a chat with Oppie on the commuter train. John von Neumann Many pure mathematicians I knew well—like Szolem or Paul Lévy—were not attuned to other fields. John von Neumann (1903–57) was a man of many trades—all sought after—and a known master of each. He continually stunned the mathematical sciences by zeroing in on problems acknowledged as the most challenging of the day, and with his speed, intellectual flexibility, and unsurpassed power, he arrived at solutions that encountered instant acclaim.

…

French Air Force Engineers Reserve Officer in Training, 1949–50 12. Growing Addiction to Classical Music, Voice, and Opera 13. Life as a Grad Student and Philips Electronics Employee, 1950–52 14. First Kepler Moment: The Zipf-Mandelbrot Distribution of Word Frequencies, 1951 15. Postdoctoral Grand Tour Begins at MIT, 1953 16. Princeton: John von Neumann’s Last Postdoc, 1953–54 17. Paris, 1954–55 18. Wooing and Marrying Aliette, 1955 19. In Geneva with Jean Piaget, Mark Kac, and Willy Feller, 1955–57 20. An Underachieving and Restless Maverick Pulls Up Shallow Roots, 1957–58 Part Three: My Life’s Fruitful Third Stage 21. At IBM Research Through Its Golden Age in the Sciences, 1958–93 22.

…

To help the biologist Jacques Monod decide between biology and music, his influential father appointed a committee. It reported that as a biologist he would match Pasteur and as a musician he would match Mozart. He chose biology and won a Nobel Prize. More important for me was the great mathematician John von Neumann, to be introduced later. Around 1920, Hungary, his motherland, was under a cloud of uncertainty far worse than Poland in 1920 and France in 1945. His rich father wanted him to play it safe and study chemical engineering, but agreed to hire a young Budapest professor named Michael Fekete to determine whether “Janos” should also be allowed to seek a Ph.D. in mathematics.

pages: 206 words: 70,924

The Rise of the Quants: Marschak, Sharpe, Black, Scholes and Merton by Colin Read

Abraham Wald, Albert Einstein, Bayesian statistics, Bear Stearns, Black-Scholes formula, Bretton Woods, Brownian motion, business cycle, capital asset pricing model, collateralized debt obligation, correlation coefficient, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, David Ricardo: comparative advantage, discovery of penicillin, discrete time, Emanuel Derman, en.wikipedia.org, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, financial engineering, financial innovation, fixed income, floating exchange rates, full employment, Henri Poincaré, implied volatility, index fund, Isaac Newton, John Meriwether, John von Neumann, Joseph Schumpeter, Kenneth Arrow, Long Term Capital Management, Louis Bachelier, margin call, market clearing, martingale, means of production, moral hazard, Myron Scholes, Paul Samuelson, price stability, principal–agent problem, quantitative trading / quantitative finance, RAND corporation, random walk, risk free rate, risk tolerance, risk/return, Robert Solow, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, Sharpe ratio, short selling, stochastic process, Thales and the olive presses, Thales of Miletus, The Chicago School, the scientific method, too big to fail, transaction costs, tulip mania, Works Progress Administration, yield curve

Nevertheless, the necessity for action and for decision compels us as practical men to do our best to overlook this awkward fact and to behave exactly as we should if we had behind us a good Benthamite calculation of a series of prospective advantages and disadvantages, each multiplied by its appropriate probability waiting to be summed.1 The finance literature further clarified that there are calculable risks and that there are uncertainties that cannot be quantified. In the 1930s, John von Neumann set about producing a model of expected utility that permitted the inclusion of risk. Then, Leonard Jimmie Savage described how our individual perceptions affect the probability of uncertainty, and Kenneth Arrow was able to include these probabilities of uncertainty in a model that established the existence of equilibrium in a market for financial securities.

…

These are the questions that the pricing analysts sought to resolve. 2 A Roadmap to Resolve the Big Questions In the first half of the twentieth century, Irving Fischer described why people save. John Maynard Keynes then showed how individuals adjust their portfolios between cash and less liquid assets, while Franco Modigliani demonstrated how all these personal financial decisions evolve over one’s lifetime. John von Neumann, Leonard Jimmie Savage, and Kenneth Arrow then incorporated uncertainty into the mix, and Harry Markowitz packaged the state of financial science into Modern Portfolio Theory. However, none of these great minds provided a satisfactory explanation for how the price of individual securities evolve over time.

…

This page intentionally left blank 3 The Early Years Jacob Marschak was not at all unusual among the cadre of great minds that formed the discipline of finance in the first half of the twentieth century. Like the families of Milton Friedman, Franco Modigliani, Leonard Jimmie Savage, Kenneth Arrow, John von Neumann, and Harry Markowitz, Marschak’s family tree was originally rooted in the Jewish culture and derived from the intellectually stimulating region of Eastern, Central and Southern Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century. This region, comprising what is now Ukraine, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and parts of Italy, was under the influence of the AustroHungarian Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

pages: 720 words: 197,129

The Innovators: How a Group of Inventors, Hackers, Geniuses and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson

1960s counterculture, Ada Lovelace, AI winter, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, AltaVista, Alvin Toffler, Apollo Guidance Computer, Apple II, augmented reality, back-to-the-land, beat the dealer, Bill Atkinson, Bill Gates: Altair 8800, bitcoin, Bletchley Park, Bob Noyce, Buckminster Fuller, Byte Shop, c2.com, call centre, Charles Babbage, citizen journalism, Claude Shannon: information theory, Clayton Christensen, commoditize, commons-based peer production, computer age, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, content marketing, crowdsourcing, cryptocurrency, Debian, desegregation, Donald Davies, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Hofstadter, driverless car, Dynabook, El Camino Real, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, en.wikipedia.org, eternal september, Evgeny Morozov, Fairchild Semiconductor, financial engineering, Firefox, Free Software Foundation, Gary Kildall, Google Glasses, Grace Hopper, Gödel, Escher, Bach, Hacker Ethic, Haight Ashbury, Hans Moravec, Howard Rheingold, Hush-A-Phone, HyperCard, hypertext link, index card, Internet Archive, Ivan Sutherland, Jacquard loom, Jaron Lanier, Jeff Bezos, jimmy wales, John Markoff, John von Neumann, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, Leonard Kleinrock, Lewis Mumford, linear model of innovation, Marc Andreessen, Mark Zuckerberg, Marshall McLuhan, Menlo Park, Mitch Kapor, Mother of all demos, Neil Armstrong, new economy, New Journalism, Norbert Wiener, Norman Macrae, packet switching, PageRank, Paul Terrell, pirate software, popular electronics, pre–internet, Project Xanadu, punch-card reader, RAND corporation, Ray Kurzweil, reality distortion field, RFC: Request For Comment, Richard Feynman, Richard Stallman, Robert Metcalfe, Rubik’s Cube, Sand Hill Road, Saturday Night Live, self-driving car, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley startup, Skype, slashdot, speech recognition, Steve Ballmer, Steve Crocker, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Steven Levy, Steven Pinker, Stewart Brand, Susan Wojcicki, technological singularity, technoutopianism, Ted Nelson, Teledyne, the Cathedral and the Bazaar, The Coming Technological Singularity, The Nature of the Firm, The Wisdom of Crowds, Turing complete, Turing machine, Turing test, value engineering, Vannevar Bush, Vernor Vinge, Von Neumann architecture, Watson beat the top human players on Jeopardy!, Whole Earth Catalog, Whole Earth Review, wikimedia commons, William Shockley: the traitorous eight, Yochai Benkler

In addition to specific notes below, this section draws on William Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing (MIT, 1990); Nancy Stern, “John von Neumann’s Influence on Electronic Digital Computing, 1944–1946,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Oct.–Dec. 1980; Stanislaw Ulam, “John von Neumann,” Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, Feb. 1958; George Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral (Random House, 2012; locations refer to Kindle edition); Herman Goldstine, The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann (Princeton, 1972; locations refer to Kindle edition). 41. Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral, 41. 42. Nicholas Vonneumann, “John von Neumann as Seen by His Brother” (Privately printed, 1987), 22, excerpted as “John von Neumann: Formative Years,” IEEE Annals, Fall 1989. 43.

…

, 161; Norman Macrae, John von Neumann (American Mathematical Society, 1992), 281. 58. Ritchie, The Computer Pioneers, 178. 59. Presper Eckert oral history, conducted by Nancy Stern, Charles Babbage Institute, Oct. 28, 1977; Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral, 1952. 60. John von Neumann, “First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC,” U.S. Army Ordnance Department and the University of Pennsylvania, June 30, 1945. The report is available at http://www.virtualtravelog.net/wp/wp-content/media/2003-08-TheFirstDraft.pdf. 61. Dyson, Turing’s Cathedral, 1957. See also Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing. 62.

…

Each tube could handle approximately a thousand bits of data at one-hundredth the cost of using a circuit of vacuum tubes. The next-generation ENIAC successor, Eckert and Mauchly wrote in a memo in the summer of 1944, should have racks of these mercury delay line tubes to store both data and rudimentary programming information in digital form. JOHN VON NEUMANN At this point, one of the most interesting characters in the history of computing reenters the tale: John von Neumann, the Hungarian-born mathematician who was a mentor to Turing in Princeton and offered him a job as an assistant. An enthusiastic polymath and urbane intellectual, he made major contributions to statistics, set theory, geometry, quantum mechanics, nuclear weapons design, fluid dynamics, game theory, and computer architecture.

pages: 589 words: 197,971

A Fiery Peace in a Cold War: Bernard Schriever and the Ultimate Weapon by Neil Sheehan

Albert Einstein, anti-communist, Berlin Wall, Boeing 747, Bretton Woods, British Empire, Charles Lindbergh, cuban missile crisis, disinformation, double helix, Dr. Strangelove, European colonialism, it's over 9,000, John von Neumann, Menlo Park, Mikhail Gorbachev, military-industrial complex, mutually assured destruction, Neil Armstrong, Norman Macrae, nuclear winter, operation paperclip, RAND corporation, Ronald Reagan, social contagion, undersea cable, uranium enrichment

BOOK IV STARTING A RACE Chapters 29–31: Schriever interviews; also interviews with Marina von Neumann Whitman and Françoise Ulam and their reminiscences at Hofstra University conference on von Neumann, May 29-June 3, 1988; interviews with Foster Evans and Jacob Wechsler; also Evans’s lecture, “Early Super Work,” published in the Los Alamos Historical Society’s 1996 Behind Tall Fences; interview with Nicholas Vonneuman and his unpublished biography of his brother, “The Legacy of John von Neumann”; John von Neumann Papers in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress; Rhodes’s The Making of the Atomic Bomb and Dark Sun; Herman Goldstine’s 1972 The Computer from Pascal to von Neumann; Stanislaw Ulam’s 1976 Adventures of a Mathematician; William Poundstone’s 1992 Prisoner’s Dilemma; Norman Macrae’s 1992 John von Neumann; and Kati Marton’s 2006 The Great Escape: Nine Jews Who Fled Hitler and Changed the World. Chapter 32: Interviews with General Schriever, Col.

…

Both Schriever and Gardner knew Ramo was indispensable for assembling the array of engineering and scientific talent needed to overcome the technological obstacles. COURTESY OF GENERAL BERNARD SCHRIEVER Cold War forgiveness: John von Neumann (right), a Jewish exile from Hitler’s Europe, conferring with Wernher von Braun, a former SS officer, Nazi Party member, and the führer’s V-2 missile man, during a visit to the Army’s Redstone Arsenal in Alabama. A mathematician and mathematical physicist with a mind second only to Albert Einstein’s, von Neumann headed the scientific advisory committee for the ICBM and lent the project his prestige. JOHN VON NEUMANN PAPERS, MANUSCRIPT DIVISION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The heartlessness of an early end: Seven months after immensely impressing Eisenhower at the July 28, 1955, White House briefing on the missile project, “Johnny” von Neumann had been driven to a wheelchair by the ravages of his cancer.

…

Chapters 72–77: Neufeld, Ballistic Missiles in the United States Air Force, 1945–1960; Heppenheimer’s Countdown; Zubok and Pleshakov, Inside the Kremlin’s Cold War; Taubman’s Khrushchev; Robert Kennedy’s 1968 Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis; Fred Kaplan’s 1983 The Wizards of Armageddon; Anatoly Dobrynin’s 1995 In Confidence; Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali’s 1997 One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958–1964; The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Ernest May and Philip Zelikow’s 1997 editing of the tapes of the White House meetings during the crisis; Max Frankel’s 2004 High Noon in the Cold War: Kennedy, Khrushchev and the Cuban Missile Crisis; Fursenko and Naftali’s 2006 Khrushchev’s Cold War; Michael Dobbs’s 2008 One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War; the official SAC history, The Development of Strategic Air Command; Wynn’s RAF Nuclear Deterrent Forces. Chapter 78: Leonid Brezhnev’s cynical remark to his brother is recounted in the 1995 memoir by his niece, Luba Brezhneva’s The World I Left Behind: Pieces of a Past. EPILOGUE THE SCHRIEVER LUCK Chapter 79: The John von Neumann Papers, Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress; Col. Vincent Ford’s memoir; Macrae’s John von Neumann; Pound-stone’s Prisoner’s Dilemma. Chapter 80: Schriever interviews; Col. Vincent Ford’s memoir; interview with Trevor Gardner, Jr. Chapter 81: November 1, 1968, historical monograph on Army Ballistic Missile Agency; Edward Hall interview.

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution That Made Computing Personal by M. Mitchell Waldrop

Ada Lovelace, air freight, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, Apple II, battle of ideas, Berlin Wall, Bill Atkinson, Bill Duvall, Bill Gates: Altair 8800, Bletchley Park, Boeing 747, Byte Shop, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, Compatible Time-Sharing System, computer age, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, conceptual framework, cuban missile crisis, Dennis Ritchie, do well by doing good, Donald Davies, double helix, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, experimental subject, Fairchild Semiconductor, fault tolerance, Frederick Winslow Taylor, friendly fire, From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death, functional programming, Gary Kildall, Haight Ashbury, Howard Rheingold, information retrieval, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, Ivan Sutherland, James Watt: steam engine, Jeff Rulifson, John von Neumann, Ken Thompson, Leonard Kleinrock, machine translation, Marc Andreessen, Menlo Park, Multics, New Journalism, Norbert Wiener, packet switching, pink-collar, pneumatic tube, popular electronics, RAND corporation, RFC: Request For Comment, Robert Metcalfe, Silicon Valley, Skinner box, Steve Crocker, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Steven Levy, Stewart Brand, Ted Nelson, The Soul of a New Machine, Turing machine, Turing test, Vannevar Bush, Von Neumann architecture, Wiener process, zero-sum game

.: Research Laboratory for Electronics, MIT, 1966), 12. 4. Steve Helms, John von Neumann and Norbert Wiener: From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1980), 206. 5. Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics, or Control and CommunicatiOn in the Animal and the Machine, 2d ed. (Cambndge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1961),23. 6. Heims, Von Neumann/Wiener, 189. 7. Norbert Wiener, "A Scientist Rebels," Atlantic Monthly, January 1947, and Bulletin of the Atomic Sci- entlSts, January 1947. 8. Helms, Von Neumann/Wiener, 334-35. 9. John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern, Theory of Games and Economic BehaviOr (Princeton, N.J.: Pnnceton University Press, 1944). 10.

…

Winston, OH 196. 484 BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS AND ARTICLES Again, the written matenals listed below are only a tiny fraction of what's avaIlable on the history of computing, but they were partICularly helpful to me in telling the story of LICk and the ARPA com- munity. Aspray, Wilham. "The SCientific ConceptualIzation of Information: A Survey." Annals of the H15tory of Computing 7 (1985). -. "John von Neumann's Contributions to Computing and Computer Science." Annals of the H15- tory of ComputIng 11, no. 3 (1989). -.John von Neumann and the Orzglns of Modern ComputIng. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1990. -. "The Intel 4004 MIcroprocessor: What Constituted Invention?" IEEE Annals of the H15tory of Computing 19, no. 3 (1997). Augarten, Stan. BIt by BIt: An Illustrated H15tory of Computers.

…

Goldstine was awestruck. Before his current incarnation-he was liaison officer for the army's computing substation at the University of Pennsylvania's Moore School of Engineering-Goldstine had been a Ph.D. mathematics instructor at the University of Michigan. So he already knew the legends. At age forty, John von Neumann (pronounced fon NaY-man) held a place in mathematics that could be compared only to that of Albert Einstein in physics. In the single year of 1927, for example, while still a mere instructor at the University of Berlin, von Neumann had put the newly emerging theory of quantum mechanics on a rigorous mathematical footing; established new links between formal logical systems and the foundations of mathematics; and cre- ated a whole new branch of mathematics known as game theory, a way of ana- lyzing how people make decisions when they are competing with each other (among other things, this field gave us the term "zero-sum game").

pages: 339 words: 94,769

Possible Minds: Twenty-Five Ways of Looking at AI by John Brockman

AI winter, airport security, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Alignment Problem, AlphaGo, artificial general intelligence, Asilomar, autonomous vehicles, basic income, Benoit Mandelbrot, Bill Joy: nanobots, Bletchley Park, Buckminster Fuller, cellular automata, Claude Shannon: information theory, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, CRISPR, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, Danny Hillis, data science, David Graeber, deep learning, DeepMind, Demis Hassabis, easy for humans, difficult for computers, Elon Musk, Eratosthenes, Ernest Rutherford, fake news, finite state, friendly AI, future of work, Geoffrey Hinton, Geoffrey West, Santa Fe Institute, gig economy, Hans Moravec, heat death of the universe, hype cycle, income inequality, industrial robot, information retrieval, invention of writing, it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it, James Watt: steam engine, Jeff Hawkins, Johannes Kepler, John Maynard Keynes: Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, John Maynard Keynes: technological unemployment, John von Neumann, Kevin Kelly, Kickstarter, Laplace demon, Large Hadron Collider, Loebner Prize, machine translation, market fundamentalism, Marshall McLuhan, Menlo Park, military-industrial complex, mirror neurons, Nick Bostrom, Norbert Wiener, OpenAI, optical character recognition, paperclip maximiser, pattern recognition, personalized medicine, Picturephone, profit maximization, profit motive, public intellectual, quantum cryptography, RAND corporation, random walk, Ray Kurzweil, Recombinant DNA, Richard Feynman, Rodney Brooks, self-driving car, sexual politics, Silicon Valley, Skype, social graph, speech recognition, statistical model, Stephen Hawking, Steven Pinker, Stewart Brand, strong AI, superintelligent machines, supervolcano, synthetic biology, systems thinking, technological determinism, technological singularity, technoutopianism, TED Talk, telemarketer, telerobotics, The future is already here, the long tail, the scientific method, theory of mind, trolley problem, Turing machine, Turing test, universal basic income, Upton Sinclair, Von Neumann architecture, Whole Earth Catalog, Y2K, you are the product, zero-sum game

The history of computing can be divided into an Old Testament and a New Testament: before and after electronic digital computers and the codes they spawned proliferated across the Earth. The Old Testament prophets, who delivered the underlying logic, included Thomas Hobbes and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The New Testament prophets included Alan Turing, John von Neumann, Claude Shannon, and Norbert Wiener. They delivered the machines. Alan Turing wondered what it would take for machines to become intelligent. John von Neumann wondered what it would take for machines to self-reproduce. Claude Shannon wondered what it would take for machines to communicate reliably, no matter how much noise intervened. Norbert Wiener wondered how long it would take for machines to assume control.

…

Since the original of The Human Use of Human Beings is now out of print, lost to us is Wiener’s cri de coeur, more relevant today than when he wrote it sixty-eight years ago: “We must cease to kiss the whip that lashes us.” MIND, THINKING, INTELLIGENCE Among the reasons we don’t hear much about cybernetics today, two are central: First, although The Human Use of Human Beings was considered an important book in its time, it ran counter to the aspirations of many of Wiener’s colleagues, including John von Neumann and Claude Shannon, who were interested in the commercialization of the new technologies. Second, computer pioneer John McCarthy disliked Wiener and refused to use Wiener’s term “Cybernetics.” McCarthy, in turn, coined the term “artificial intelligence” and became a founding father of that field.

…

In my own work with experimentalists on building quantum computers, I typically find that some of the technological steps I expect to be easy turn out to be impossible, whereas some of the tasks I imagine to be impossible turn out to be easy. You don’t know until you try. In the 1950s, partly inspired by conversations with Wiener, John von Neumann introduced the notion of the “technological singularity.” Technologies tend to improve exponentially, doubling in power or sensitivity over some interval of time. (For example, since 1950, computer technologies have been doubling in power roughly every two years, an observation enshrined as Moore’s Law.)

pages: 360 words: 85,321

The Perfect Bet: How Science and Math Are Taking the Luck Out of Gambling by Adam Kucharski

Ada Lovelace, Albert Einstein, Antoine Gombaud: Chevalier de Méré, beat the dealer, behavioural economics, Benoit Mandelbrot, Bletchley Park, butterfly effect, call centre, Chance favours the prepared mind, Claude Shannon: information theory, collateralized debt obligation, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, correlation does not imply causation, diversification, Edward Lorenz: Chaos theory, Edward Thorp, Everything should be made as simple as possible, Flash crash, Gerolamo Cardano, Henri Poincaré, Hibernia Atlantic: Project Express, if you build it, they will come, invention of the telegraph, Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, John Nash: game theory, John von Neumann, locking in a profit, Louis Pasteur, Nash equilibrium, Norbert Wiener, p-value, performance metric, Pierre-Simon Laplace, probability theory / Blaise Pascal / Pierre de Fermat, quantitative trading / quantitative finance, random walk, Richard Feynman, Ronald Reagan, Rubik’s Cube, statistical model, The Design of Experiments, Watson beat the top human players on Jeopardy!, zero-sum game

Review of Economic Studies 70 (2003): 395–415. 147Von Neumann completed his solution: Details of the dispute were given in: Kjedldsen, T. H. “John von Neumann’s Conception of the Minimax Theorem: A Journey Through Different Mathematical Contexts.” Archive for History of Exact Science 56 (2001). 149While earning his master’s degree in 2003: Follek, Robert. “Soar-Bot: A Rule-Based System for Playing Poker” (MSc diss., School of Computer Science and Information Systems, Pace University, 2003). 150Led by David Hilbert: O’Connor, J. J., and E. F. Robertson. “Biography of John von Neumann.” JOC/EFR, October 2003. http://www-history.mcs.st-and.ac.uk/Biographies/Von_Neumann.html. 150some inconsistencies in the US Constitution: “Kurt Gödel.”

…

Faced with having to calculate a vast set of possibilities—the sort of monotonous work he usually tried to avoid—Ulam realized it might be quicker just to lay out the cards several times and watch what happened. If he repeated the experiment enough times, he would end up with a good idea of the answer without doing a single calculation. Wondering whether the same technique could also help with the neutron problem, Ulam took the idea to one of his closest colleagues, a mathematician by the name of John von Neumann. The two had known each other for over a decade. It was von Neumann who’d suggested Ulam leave Poland for America in the 1930s; he’d also been the one who invited Ulam to join Los Alamos in 1943. They made quite the pair, portly von Neumann in his immaculate suits—jacket always on—and Ulam with his absent-minded fashion sense and dazzling green eyes.

…

Substitute talking and silence for advertising and cutting promotions, and it is the same problem the advertising firms faced. Nash received his PhD in 1950, for a twenty-seven-page thesis describing how his equilibrium can sometimes thwart seemingly beneficial outcomes. But Nash wasn’t the first person to take a mathematical hammer to the problem of competitive games. History has given that accolade to John von Neumann. Although later known for his time at Los Alamos and Princeton, in 1926 von Neumann was a young lecturer at the University of Berlin. In fact, he was the youngest in its history. Despite his prodigious academic record, however, there were still some things he wasn’t very good at. One of them was poker.

pages: 288 words: 81,253

Thinking in Bets by Annie Duke

banking crisis, behavioural economics, Bernie Madoff, Cass Sunstein, cognitive bias, cognitive dissonance, cognitive load, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, delayed gratification, Demis Hassabis, disinformation, Donald Trump, Dr. Strangelove, en.wikipedia.org, endowment effect, Estimating the Reproducibility of Psychological Science, fake news, Filter Bubble, Herman Kahn, hindsight bias, Jean Tirole, John Nash: game theory, John von Neumann, loss aversion, market design, mutually assured destruction, Nate Silver, p-value, phenotype, prediction markets, Richard Feynman, ride hailing / ride sharing, Stanford marshmallow experiment, Stephen Hawking, Steven Pinker, systematic bias, TED Talk, the scientific method, The Signal and the Noise by Nate Silver, urban planning, Walter Mischel, Yogi Berra, zero-sum game

The information about von Neumann, in addition to the sources mentioned in the section (which are cited in the Selected Bibliography and Recommendations for Further Reading), are from the following sources: Boston Public Library, “100 Most Influential Books of the Century,” posted on TheGreatestBooks.org; Tim Hartford, “A Beautiful Theory,” Forbes, December 10, 2006; Institute for Advanced Study, “John von Neumann’s Legacy,” IAS.edu; Alexander Leitch, “von Neumann, John,” A Princeton Companion (1978); Robert Leonard, “From Parlor Games to Social Science: von Neumann, Morgenstern, and the Creation of Game Theory 1928–1944,” Journal of Economic Literature (1995). The quotes from reviews that greeted Theory of Games are from Harold W. Kuhn’s introduction to the sixtieth anniversary edition. The influences behind the title character in Dr. Strangelove either are alluringly vague or differ based on who’s telling (or speculating). John von Neumann shared a number of physical characteristcs with the character and is usually cited as an influence.

…

That makes poker a great place to find innovative approaches to overcoming this struggle. And the value of poker in understanding decision-making has been recognized in academics for a long time. Dr. Strangelove It’s hard for a scientist to become a household name. So it shouldn’t be surprising that for most people the name John von Neumann doesn’t ring a bell. That’s a shame because von Neumann is a hero of mine, and should be to anyone committed to making better decisions. His contributions to the science of decision-making were immense, and yet they were just a footnote in the short life of one of the greatest minds in the history of scientific thought.

…

Strangelove: a heavily accented, crumpled, wheelchair-bound genius whose strategy of relying on mutually assured destruction goes awry when an insane general sends a single bomber on an unauthorized mission that could trigger the automated firing of all American and Soviet nuclear weapons. In addition to everything else he accomplished, John von Neumann is also the father of game theory. After finishing his day job on the Manhattan Project, he collaborated with Oskar Morgenstern to publish Theory of Games and Economic Behavior in 1944. The Boston Public Library’s list of the “100 Most Influential Books of the Century” includes Theory of Games.

pages: 518 words: 107,836

How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet (Information Policy) by Benjamin Peters

Albert Einstein, American ideology, Andrei Shleifer, Anthropocene, Benoit Mandelbrot, bitcoin, Brownian motion, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, cloud computing, cognitive dissonance, commons-based peer production, computer age, conceptual framework, continuation of politics by other means, crony capitalism, crowdsourcing, cuban missile crisis, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, David Graeber, disinformation, Dissolution of the Soviet Union, Donald Davies, double helix, Drosophila, Francis Fukuyama: the end of history, From Mathematics to the Technologies of Life and Death, Gabriella Coleman, hive mind, index card, informal economy, information asymmetry, invisible hand, Jacquard loom, John von Neumann, Kevin Kelly, knowledge economy, knowledge worker, Lewis Mumford, linear programming, mandelbrot fractal, Marshall McLuhan, means of production, megaproject, Menlo Park, Mikhail Gorbachev, military-industrial complex, mutually assured destruction, Network effects, Norbert Wiener, packet switching, Pareto efficiency, pattern recognition, Paul Erdős, Peter Thiel, Philip Mirowski, power law, RAND corporation, rent-seeking, road to serfdom, Ronald Coase, scientific mainstream, scientific management, Steve Jobs, Stewart Brand, stochastic process, surveillance capitalism, systems thinking, technoutopianism, the Cathedral and the Bazaar, the strength of weak ties, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, transaction costs, Turing machine, work culture , Yochai Benkler

Wiener, Cybernetics, 1–25, 155–168. 8. Ibid., 16. 9. Dupuy, Mechanization of the Mind. See also John von Neumann, The Computer and the Brain, 2nd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, [1958] 2000). 10. Quoted in Claus Pias, “Analog, Digital, and the Cybernetic Illusion,” Kybernetes 34 (3–4) (2005): 544. 11. Claus Pias, ed., Cybernetics-Kybernetik 2: The Macy-Conferences 1946–1953 (Berlin: Diaphanes, 2004). 12. Steve J. Heims, The Cybernetics Group (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991). 13. Ibid., 52–53, 207. 14. William Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990). 15. David Lipset, Gregory Bateson: The Legacy of a Scientist (New York: Prentice Hall, 1980).

…

Borrowing from the language of Hannah Arendt, it recasts the Soviet network experience in light of other national network projects in the latter half of the twentieth century, suggesting the ways that the Soviet experience may appear uncomfortably close to our modern network situation. A few other summary observations for scholar and general-interest reader are offered in close. 1 A Global History of Cybernetics I am thinking about something much more important than bombs. I am thinking about computers. —John von Neumann, 1946 Cybernetics nursed early national computer network projects on both sides of the cold war. Cybernetics was a postwar systems science concerned with communication and control—and although its significance has been well documented in the history of science and technology, its implications as a carrier of early ideas about and language for computational communication have been largely neglected by communication and media scholars.1 This chapter discusses how cybernetics became global early in the cold war, coalescing first in postwar America before diffusing to other parts of the world, especially Soviet Union after Stalin’s death in 1953, as well as how Soviet cybernetics shaped the scientific regime for governing economics that eventually led to the nationwide network projects imagined in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

…

Foundation in New York City. The Macy Conferences, as they were informally known, staked out a spacious interdisciplinary purview for cybernetic research.11 In addition to McCulloch, who directed the conferences, a few noted participants included Wiener himself, the mathematician and game theorist John von Neumann, leading anthropologist Margaret Mead and her then husband Gregory Bateson, founding information theorist and engineer Claude Shannon, sociologist-statistician and communication theorist Paul Lazarsfeld, psychologist and computer scientist J.C.R. Licklider, as well as influential psychiatrists, psychoanalysts, and philosophers such as Kurt Lewin, F.S.C.

pages: 528 words: 146,459

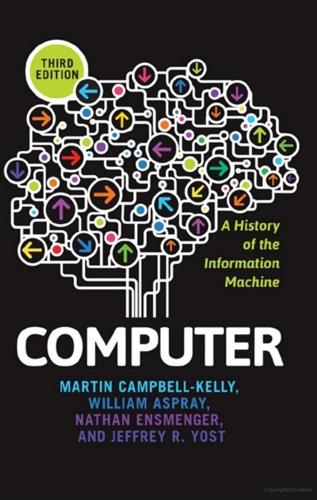

Computer: A History of the Information Machine by Martin Campbell-Kelly, William Aspray, Nathan L. Ensmenger, Jeffrey R. Yost

Ada Lovelace, air freight, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Apple's 1984 Super Bowl advert, barriers to entry, Bill Gates: Altair 8800, Bletchley Park, borderless world, Buckminster Fuller, Build a better mousetrap, Byte Shop, card file, cashless society, Charles Babbage, cloud computing, combinatorial explosion, Compatible Time-Sharing System, computer age, Computer Lib, deskilling, don't be evil, Donald Davies, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, Edward Jenner, Evgeny Morozov, Fairchild Semiconductor, fault tolerance, Fellow of the Royal Society, financial independence, Frederick Winslow Taylor, game design, garden city movement, Gary Kildall, Grace Hopper, Herman Kahn, hockey-stick growth, Ian Bogost, industrial research laboratory, informal economy, interchangeable parts, invention of the wheel, Ivan Sutherland, Jacquard loom, Jeff Bezos, jimmy wales, John Markoff, John Perry Barlow, John von Neumann, Ken Thompson, Kickstarter, light touch regulation, linked data, machine readable, Marc Andreessen, Mark Zuckerberg, Marshall McLuhan, Menlo Park, Mitch Kapor, Multics, natural language processing, Network effects, New Journalism, Norbert Wiener, Occupy movement, optical character recognition, packet switching, PageRank, PalmPilot, pattern recognition, Pierre-Simon Laplace, pirate software, popular electronics, prediction markets, pre–internet, QWERTY keyboard, RAND corporation, Robert X Cringely, Salesforce, scientific management, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley startup, Steve Jobs, Steven Levy, Stewart Brand, Ted Nelson, the market place, Turing machine, Twitter Arab Spring, Vannevar Bush, vertical integration, Von Neumann architecture, Whole Earth Catalog, William Shockley: the traitorous eight, women in the workforce, young professional

Licklider was a consummate political operator who motivated a generation of computer scientists and obtained government funding for them to work in the fields of human-computer interaction and networked computing. COURTESY OF MIT MUSEUM. Working at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, Herman Goldstine and John von Neumann introduced the “flow diagram” (above) as a way of managing the complexity of programs and communicating them to others. COURTESY OF INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY, PRINCETON: Herman H. Goldstine and John von Neumann, Planning and Coding of Problems for an Electronic Computing Instrument, Part II, Volume 2 (1948), p. 28. Programming languages, such as FORTRAN, COBOL, and BASIC, improved the productivity of programmers and enabled nonexperts to write programs.

…