The Home Computer Revolution

10 results back to index

pages: 352 words: 120,202

Tools for Thought: The History and Future of Mind-Expanding Technology by Howard Rheingold

Ada Lovelace, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Bletchley Park, card file, cellular automata, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, combinatorial explosion, Compatible Time-Sharing System, computer age, Computer Lib, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, conceptual framework, Conway's Game of Life, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, experimental subject, Hacker Ethic, heat death of the universe, Howard Rheingold, human-factors engineering, interchangeable parts, invention of movable type, invention of the printing press, Ivan Sutherland, Jacquard loom, John von Neumann, knowledge worker, machine readable, Marshall McLuhan, Menlo Park, Neil Armstrong, Norbert Wiener, packet switching, pattern recognition, popular electronics, post-industrial society, Project Xanadu, RAND corporation, Robert Metcalfe, Silicon Valley, speech recognition, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Stewart Brand, Ted Nelson, telemarketer, The Home Computer Revolution, Turing machine, Turing test, Vannevar Bush, Von Neumann architecture

Another computer prophet who saw the implications of Sketchpad and other heretofore esoteric wonders of personal computing was an irreverent, unorthodox, counterculture fellow by the name of Ted Nelson, who has long been in the habit of self-publishing quirky, cranky, amazingly accurate commentaries on the future of computing. In The Home Computer Revolution Nelson had this to say about Sutherland's pioneering program, in a chapter entitled "The most important computer Program Ever Written": You could draw a picture on the screen with the lightpen -- and then file the picture away in the computer's memory. You could, indeed, save numerous pictures in this way.

…

But the idea people in universities and corporate laboratories, the research and development pioneers who made the technology possible, were not the only contemporaries whom Nelson watched and applauded in the mid 1970s as they streaked past him on their way to somewhere. As had happened so often before, some unknown young people appeared from an unexpected quarter to create a new way to use the formerly esoteric machinery. The legend is firmly established by now, and Ted was the first to chronicle it, in The Home Computer Revolution. By the mid-1970s the state of integrated circuitry had reached such a high degree of miniaturization that it was possible to make electronic components thousands of times more complicated than ENIAC -- except these machines didn't heat a warehouse to 120 degrees. In fact, they tended to get lost if you dropped them on the rug.

…

Unlike many of the more sheltered academics, he also saw the potential of a hobbyist "underground." Nelson chose to bypass (and thereby antagonize) both the academic and industrial computerists by appealing directly to the public in a series of self-published tracts that railed against the pronouncements of the programming priesthood. Nelson's books, Computer Lib, The Home Computer Revolution, and Literary Machines, not only gave the orthodoxy blatant Bronx Cheers -- they also ventured dozens of predictions about the future of personal computers, many of which turned out to be strikingly accurate, a few of which turned out to be bad guesses. As a forecaster in a notoriously unpredictable field, Ted Nelson has done better than most -- at forecasting.

They Have a Word for It A Lighthearted Lexicon of Untranslatable Words & Phrases-Sarabande Books (2000) by Howard Rheingold

Ayatollah Khomeini, clockwork universe, Easter island, fudge factor, Howard Rheingold, informal economy, junk bonds, Kula ring, Lao Tzu, Ronald Reagan, Rosa Parks, Silicon Valley, systems thinking, The Home Computer Revolution, the map is not the territory, the scientific method, Tragedy of the Commons

The result is that we are building more and more powerful machines, but fewer and fewer people can figure out how to operate them! That's where the new and growing role of animateur ( on-ee- 240 THEY HAVE A WORD FOR IT maht-HER with "H" silent) comes in. The problem has been brewing for a long time, but the home computer revolution-or, rather, the failure of the home computer revolution-has brought it out into the general consciousness. When the personal-computer boom started in the early 1980s, market forecasts were wildly optimistic. The professional prognosticators looked at the initial sales figures and predicted that every home in America would have a computer within a few years.

pages: 223 words: 52,808

Intertwingled: The Work and Influence of Ted Nelson (History of Computing) by Douglas R. Dechow

3D printing, Apple II, Bill Duvall, Brewster Kahle, Buckminster Fuller, Claude Shannon: information theory, cognitive dissonance, computer age, Computer Lib, conceptual framework, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, Edward Snowden, game design, HyperCard, hypertext link, Ian Bogost, information retrieval, Internet Archive, Ivan Sutherland, Jaron Lanier, knowledge worker, linked data, Marc Andreessen, Marshall McLuhan, Menlo Park, Mother of all demos, pre–internet, Project Xanadu, RAND corporation, semantic web, Silicon Valley, software studies, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Stewart Brand, Ted Nelson, TED Talk, The Home Computer Revolution, the medium is the message, Vannevar Bush, Wall-E, Whole Earth Catalog

In: ACPA-5: papers presented at the 5th conference – association of computer programmers and analysts *Nelson TH (1976) [Television]. Chicago, January, 106. Untitled contribution to section called “Television,” originally submitted under the title “Explorable Screens” Nelson TH (1977) The home computer revolution. In: Nelson TH (ed) South Bend, Ind.; distributed by the Distributors Nelson TH (1977) A dream for Irving Snerd. Creat Comput May–June, 79–81. Xanadu introduced in cartoon format. (Reprinted in The best of creative computing, vol. 3 (1980), 24–26) Nelson TH (1977) PCC interviews Ted Nelson.

pages: 244 words: 66,599

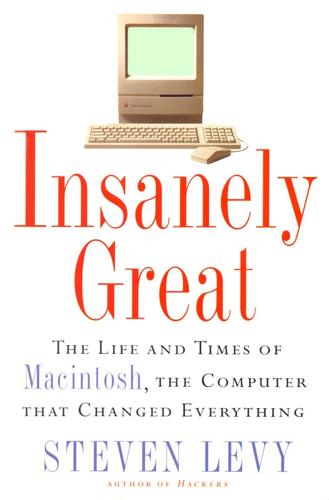

Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything by Steven Levy

Apple II, Apple's 1984 Super Bowl advert, Bill Atkinson, computer age, Computer Lib, conceptual framework, Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life?, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, General Magic , Howard Rheingold, HyperCard, information retrieval, information trail, Ivan Sutherland, John Markoff, John Perry Barlow, Kickstarter, knowledge worker, Marshall McLuhan, Mitch Kapor, Mother of all demos, Pepsi Challenge, Productivity paradox, QWERTY keyboard, reality distortion field, rolodex, Silicon Valley, skunkworks, speech recognition, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Steven Levy, Ted Nelson, The Home Computer Revolution, the medium is the message, Vannevar Bush

But few had imagined that this rough beast of a calculating engine could be transmogrified into a sophisticated system to create shapes, pictures, and blueprints. And when you created your shapes you could copy them, alter them, or store them. In 1977, Ted Nelson (whom we will meet when our story turns to HyperCard) gushed about Sutherland's wonder-"The Most Important Computer Program Ever Written," he called it-in his book The Home Computer Revolution .. . . working on a screen you could try out things you couldn't tryout as a draftsman on paper. You were concerning yourself with an abstracted version of the drafting problem; you didn't have to sharpen any pencils, or prepare a sheet to draw on, or use a T-square or an eraser. All these functions were built into the program in ways that you could use through the flick of a switch or the pointing of the light pen.

pages: 247 words: 81,135

The Great Fragmentation: And Why the Future of All Business Is Small by Steve Sammartino

3D printing, additive manufacturing, Airbnb, augmented reality, barriers to entry, behavioural economics, Bill Gates: Altair 8800, bitcoin, BRICs, Buckminster Fuller, citizen journalism, collaborative consumption, cryptocurrency, data science, David Heinemeier Hansson, deep learning, disruptive innovation, driverless car, Dunbar number, Elon Musk, fiat currency, Frederick Winslow Taylor, game design, gamification, Google X / Alphabet X, haute couture, helicopter parent, hype cycle, illegal immigration, index fund, Jeff Bezos, jimmy wales, Kickstarter, knowledge economy, Law of Accelerating Returns, lifelogging, market design, Mary Meeker, Metcalfe's law, Minecraft, minimum viable product, Network effects, new economy, peer-to-peer, planned obsolescence, post scarcity, prediction markets, pre–internet, profit motive, race to the bottom, random walk, Ray Kurzweil, recommendation engine, remote working, RFID, Rubik’s Cube, scientific management, self-driving car, sharing economy, side project, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley startup, skunkworks, Skype, social graph, social web, software is eating the world, Steve Jobs, subscription business, survivorship bias, The Home Computer Revolution, the long tail, too big to fail, US Airways Flight 1549, vertical integration, web application, zero-sum game

It’s the way it’s always been, excluding the 200-year halcyon period of the industrial era. Dad vs daughter I’ve been thrilled to own a 3D printer for a few years now. I purchased one when they hit their Altair moment (the Altair 8800 is regarded as the first affordable personal computer and the spark of the home computer revolution). It’s a pretty impressive party trick introducing someone to the basic idea of 3D printing, helping them work through their initial incredulity, showing them a little video about it, and then helping them print their first item. It’s a social experiment I’ve undertaken on both my 70-year-old father and my four-year-old daughter.

pages: 405 words: 105,395

Empire of the Sum: The Rise and Reign of the Pocket Calculator by Keith Houston

Ada Lovelace, Alan Turing: On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, Andy Kessler, Apollo 11, Apollo 13, Apple II, Bletchley Park, Boris Johnson, Charles Babbage, classic study, clockwork universe, computer age, Computing Machinery and Intelligence, double entry bookkeeping, Edmond Halley, Fairchild Semiconductor, Fellow of the Royal Society, Grace Hopper, human-factors engineering, invention of movable type, invention of the telephone, Isaac Newton, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Johannes Kepler, John Markoff, John von Neumann, Jony Ive, Kickstarter, machine readable, Masayoshi Son, Menlo Park, meta-analysis, military-industrial complex, Mitch Kapor, Neil Armstrong, off-by-one error, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, orbital mechanics / astrodynamics, pattern recognition, popular electronics, QWERTY keyboard, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Robert X Cringely, side project, Silicon Valley, skunkworks, SoftBank, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, The Home Computer Revolution, the payments system, Turing machine, Turing test, V2 rocket, William Shockley: the traitorous eight, Works Progress Administration, Yom Kippur War

During the 1970s, electronics, computing, and software were evolving so rapidly that the calculator was caught up in a jumble of cause and effect. For a flavor of that foment, consider that Apple’s co-founders, Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, met at HP during that company’s push into calculators. The Steves’ early microcomputers, the Apple and Apple II, helped spark the home-computer revolution, which in turn gave Dan Bricklin the opportunity to perfect the first computerized spreadsheet. Mitch Kapor, who had worked for Bricklin’s publisher, stole the spreadsheet crown with his own program, Lotus 1-2-3, and with it gave the IBM PC one of its first killer apps. That PC, of course, was powered by an Intel CPU—a chip made by the same company whose deal with Busicom, a Japanese calculator manufacturer, had saved the American firm and paved the way for the founding of Silicon Valley.

pages: 744 words: 142,748

Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell by Phil Lapsley

air freight, Apple II, Bill Gates: Altair 8800, Bob Noyce, card file, classic study, cuban missile crisis, dumpster diving, Garrett Hardin, Hush-A-Phone, index card, Jason Scott: textfiles.com, John Markoff, Menlo Park, military-industrial complex, Neal Stephenson, popular electronics, Richard Feynman, Saturday Night Live, Silicon Valley, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Steven Levy, The Home Computer Revolution, the new new thing, the scientific method, Tragedy of the Commons, undersea cable, urban renewal, wikimedia commons

By 1974 Intel had released a new and greatly improved successor, the Intel 8080, a tiny rectangle of silicon some 3/16 of an inch on a side that contained about six thousand transistors. It was a computer on a chip that executed a few hundred thousand instructions per second. Engineers called it the “first truly useable microprocessor.” Intel didn’t know it yet but that chip would be the thing that started the home computer revolution and would lead to Intel’s eventual domination of the microprocessor market. In January 1975 Popular Electronics, a geeky electronic hobbyist magazine, offered its readers an unbelievable chance to own their own slice of high-tech heaven. “Project Breakthrough!” the cover fairly shouted.

pages: 598 words: 150,801

Snakes and Ladders: The Great British Social Mobility Myth by Selina Todd

assortative mating, Bletchley Park, Boris Johnson, collective bargaining, conceptual framework, coronavirus, COVID-19, deindustrialization, deskilling, DIY culture, emotional labour, Etonian, fear of failure, feminist movement, financial independence, full employment, Gini coefficient, greed is good, housing crisis, income inequality, Jeremy Corbyn, Kickstarter, Mahatma Gandhi, manufacturing employment, meritocracy, Nick Leeson, offshore financial centre, old-boy network, profit motive, rent control, Right to Buy, school choice, social distancing, statistical model, The Home Computer Revolution, The Spirit Level, traveling salesman, unpaid internship, upwardly mobile, urban sprawl, women in the workforce, Yom Kippur War, young professional

Instead he found himself spending nights completing his work: he found the course both ‘hard’ and boring, and only completed it ‘out of duty’. But when Paul passed, he found that, most disappointingly of all, the hoped-for jobs didn’t exist. While he had been studying, ‘computing had become ubiquitous’. There was no need for large numbers of highly trained programmers as the home computer revolution began. Basing education on current technology was as short-sighted in the 1980s as it had been in the technical schools of the 1950s. Paul became a support worker in air traffic control, but he found the job unsatisfying and was aware that he ‘didn’t need a degree to get it.’20 He remained in this line of work for the rest of his career

The Big Score by Michael S. Malone

Apple II, Bob Noyce, bread and circuses, Buckminster Fuller, Byte Shop, Charles Babbage, Claude Shannon: information theory, computer age, creative destruction, Donner party, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, El Camino Real, Fairchild Semiconductor, fear of failure, financial independence, game design, Isaac Newton, job-hopping, lone genius, market bubble, Menlo Park, military-industrial complex, packet switching, plutocrats, RAND corporation, ROLM, Ronald Reagan, Salesforce, Sand Hill Road, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley startup, speech recognition, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, tech worker, Teledyne, The Home Computer Revolution, transcontinental railway, Turing machine, union organizing, Upton Sinclair, upwardly mobile, William Shockley: the traitorous eight, Yom Kippur War

Kassar made frequent appearances in the society pages of the San Francisco Chronicle and was often mentioned in Herb Caen’s column (perhaps to return the favor, Atari employed Caen’s son as a summer intern). The great tragedy of it all was that if any firm had the opportunity to inaugurate the home computer revolution it was Atari. The home market is the fata morgana of the electronics business—a beautiful vision when approached dissipates and leaves only disaster on the rocks. Nevertheless, Atari, if anyone, could still have burst open the door to the family market, making a computer the latest home appliance—and, for that matter, could have made for itself a magnificent alternate business as games fell away.

pages: 636 words: 202,284

Piracy : The Intellectual Property Wars from Gutenberg to Gates by Adrian Johns

active measures, Alan Greenspan, banking crisis, Berlin Wall, British Empire, Buckminster Fuller, business intelligence, Charles Babbage, commoditize, Computer Lib, Corn Laws, demand response, distributed generation, Douglas Engelbart, Douglas Engelbart, Edmond Halley, Ernest Rutherford, Fellow of the Royal Society, full employment, Hacker Ethic, Howard Rheingold, industrial research laboratory, informal economy, invention of the printing press, Isaac Newton, James Watt: steam engine, John Harrison: Longitude, Lewis Mumford, Marshall McLuhan, Mont Pelerin Society, new economy, New Journalism, Norbert Wiener, pirate software, radical decentralization, Republic of Letters, Richard Stallman, road to serfdom, Ronald Coase, software patent, South Sea Bubble, Steven Levy, Stewart Brand, tacit knowledge, Ted Nelson, The Home Computer Revolution, the scientific method, traveling salesman, vertical integration, Whole Earth Catalog

Much of its TV terminal ware originated in a design Wozniak had come up with a year earlier to help Draper hack into Arpanet, however. And some of the video circuitry ultimately derived from his own phreaking box. Not only was the Apple II a cultural emanation of the conjunction of hacking and phreaking, therefore; the machine itself that launched the home computer revolution owed a debt to phreak technologies. Moreover, Draper now became one of Apple’s first employees. He was given the task of designing a telephone interface for the hotselling computer. When he produced something that looked just like a phreak’s blue box, however, the young company forthwith scrapped it and dismissed him.

pages: 915 words: 232,883

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson

"World Economic Forum" Davos, air freight, Albert Einstein, Andy Rubin, AOL-Time Warner, Apollo 13, Apple II, Apple's 1984 Super Bowl advert, big-box store, Bill Atkinson, Bob Noyce, Buckminster Fuller, Byte Shop, centre right, Clayton Christensen, cloud computing, commoditize, computer age, computer vision, corporate governance, death of newspapers, Do you want to sell sugared water for the rest of your life?, don't be evil, Douglas Engelbart, Dynabook, El Camino Real, Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Fairchild Semiconductor, Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, fixed income, game design, General Magic , Golden Gate Park, Hacker Ethic, hiring and firing, It's morning again in America, Jeff Bezos, Johannes Kepler, John Markoff, Jony Ive, Kanban, Larry Ellison, lateral thinking, Lewis Mumford, Mark Zuckerberg, Menlo Park, Mitch Kapor, Mother of all demos, Paul Terrell, Pepsi Challenge, profit maximization, publish or perish, reality distortion field, Recombinant DNA, Richard Feynman, Robert Metcalfe, Robert X Cringely, Ronald Reagan, Silicon Valley, skunkworks, Steve Ballmer, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, Steven Levy, Stewart Brand, supply-chain management, The Home Computer Revolution, thinkpad, Tim Cook: Apple, Tony Fadell, vertical integration, Wall-E, Whole Earth Catalog

Jobs did both, relentlessly. As a result he launched a series of products over three decades that transformed whole industries: • The Apple II, which took Wozniak’s circuit board and turned it into the first personal computer that was not just for hobbyists. • The Macintosh, which begat the home computer revolution and popularized graphical user interfaces. • Toy Story and other Pixar blockbusters, which opened up the miracle of digital imagination. • Apple stores, which reinvented the role of a store in defining a brand. • The iPod, which changed the way we consume music. • The iTunes Store, which saved the music industry