liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view

19 results back to index

pages: 576 words: 105,655

Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea by Mark Blyth

"there is no alternative" (TINA), accounting loophole / creative accounting, Alan Greenspan, balance sheet recession, bank run, banking crisis, Bear Stearns, Black Swan, book value, Bretton Woods, business cycle, buy and hold, capital controls, Carmen Reinhart, Celtic Tiger, central bank independence, centre right, collateralized debt obligation, correlation does not imply causation, creative destruction, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, currency peg, debt deflation, deindustrialization, disintermediation, diversification, en.wikipedia.org, ending welfare as we know it, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, eurozone crisis, financial engineering, financial repression, fixed income, floating exchange rates, Fractional reserve banking, full employment, German hyperinflation, Gini coefficient, global reserve currency, Greenspan put, Growth in a Time of Debt, high-speed rail, Hyman Minsky, income inequality, information asymmetry, interest rate swap, invisible hand, Irish property bubble, Joseph Schumpeter, Kenneth Rogoff, liberal capitalism, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, market bubble, market clearing, Martin Wolf, Minsky moment, money market fund, moral hazard, mortgage debt, mortgage tax deduction, Occupy movement, offshore financial centre, paradox of thrift, Philip Mirowski, Phillips curve, Post-Keynesian economics, price stability, quantitative easing, rent-seeking, reserve currency, road to serfdom, Robert Solow, savings glut, short selling, structural adjustment programs, tail risk, The Great Moderation, The Myth of the Rational Market, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Tobin tax, too big to fail, Two Sigma, unorthodox policies, value at risk, Washington Consensus, zero-sum game

The tension between these two viewpoints—can’t live with it, can’t live without it—generates a concern with how states should fund themselves, and it is this concern that creates the conditions for the emergence of austerity as a distinct economic doctrine when states become large enough budgetary entities in their own right to warrant cutting: that is, by the 1920s. When that happens, austerity appears in its own right as a distinct economic doctrine. After briefly detailing some nineteenth- and early twentieth-century precursors, I examine the two key austerity doctrines formed in this period: “liquidationism”—sometimes called “the Banker’s doctrine” in the United States—and the “Treasury view” in the United Kingdom. These ideas were, I argue, the original neoliberal ideas in that they drew on the classical liberalism of Locke, Hume, and Smith, and applied themselves anew to the policy issues of the day. I then discuss the responses that these ideas engendered, the most relevant of which are John Maynard Keynes’s refutation of austerity policies and Joseph Schumpeter’s strange abrogation of them.11 By 1942, it seems that the die has been cast and austerity had been sent away to the retirement home for bad economic ideas.

…

., 168 Sweden as a welfare state, 214 austerity in, 17, 178–180, 191–193, 204, 206 economic recovery in the 1930s in, 126 expansionary contraction in, 209–210, 211 fiscal adjustment in, 173 Swedish Social Democrats, (SAP), 191 thirty-year bond in, 210–211 systemic risk, 44 Tabellini, Guido “Positive Theory of Fiscal Deficits and Government Debt in a Democracy, A”, 167 tail risk, 44 See also systemic risk Takahashi, Korekiyo, 199 Taleb, Nassim Nicolas, 32, 33, 34 “Tales of Fiscal Adjustment” (Alesina and Ardanga), 171, 205, 208, 209 Target Two payments, 91 Taylor, Alan, 73 Tax Justice Network, 244 Thatcher, Margaret, 15 “there is no alternative”, 98, 171–173, 175, 231 ThyssenKrupp, 132 Tilford, Simon, 83 “too big to bail,” 49, 51–93, 74, 82 European banks as, 83, 90, 92 “too big to fail”, 6, 16, 45, 47–50, 82, 231 Tooze, Adam, 196 Trichet, Jean Claude, 60 as president of the ECB, 176 on Greece and Ireland, 235 See also European Central Bank United Kingdom, 1 and the gold standard, 185, 189–191 asset footprint of top banks, 83 austerity in, 17, 122–125, 126, 178–180 and the global economy in the 1920s and 1930s, 184–189, 189–121 banking crisis in, 52 cost of, 45 depression in, 204 Eurozone Ten-Year Government Bond Yields, 80 fig. 3.2 Gordon Brown economics policy, 5, 59 housing bubble, 66–67 Lawson boom, 208 “Memoranda on Certain Proposals Relating to Unemployment” (UK White Paper), 122, 124 New Liberalism, 117–119 “Treasury view”, 101, 163–165 war debts to the United States, 185 United States, 2 AAA credit rating, 1, 2–3 Agricultural Adjustment Act, 188 and current economic conditions, 213 and printing its own money, 11 and recycling foreign savings, 11–12 and the Austrian School of economics, 121, 143–145, 148–152 and the gold standard, 188 assets of large banks in, 6 austerity in, 17, 119–122, 178–180, 187–189 “Banker’s doctrine”, 101 banking system of, 6 cost of crisis, 45, 52 Bush administration economics policy, 5, 58–59 capital-flow cycle in, 11 Congressional Research Service (CRS), 213 debt-ceiling agreement, 3 depression in, 188 Federal Reserve, 6, 157 federal taxes, 242–243 liberalism in, 119–122 liquidationism in, 119–122, 204 National Industrial Recovery Act, 188 repo market, 15–16, 24–25 rise in real estate prices in, 27 Securities and Exchange Commission, 49 Simson-Bowles Commission, 122, 122–125 Social Security Act, 188 stimulus in, 55 stop in capital flow in 1929, 190 Treasury bills, 25 Troubled Asset Relief Program, 58–59, 230 and American politics involvement, 59 Wagner’s Act, 188 Wall Street Crash of 1929, 204, 238 Washington Consensus, 142, 161–162, 165 Value at Risk (VaR) analysis, 34–38 Vienna agreement, 221 Viniar, David, 32 Wade, Robert, 13 Wagner, Richard, 156 Wartin, Christian, 137 Watson Institute for International Studies, ix “We Can Conquer Unemployment” (Lloyd George), 123, 24 “Wealth of Nations, The”, 109, 112 welfare, xi, 58 welfare state foundation for, 117 Wells Fargo, 48 Whyte, Philip, 83 Williamson, John, 161, 162 World Bank, 163, 210, 211 World Economic Outlook, 212

…

Joan Robinson, “The Second Crisis of Economic Theory,” American Economic Review 62, 1/2 (March 1972): 2. 85. Stanley Baldwin, quoted in Keith Middlemas and John Barnes, Baldwin: A Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972) quoted in George C. Peden “The ‘Treasury View’ on Public Works and Employment in the Interwar Period,” The Economic History Review 37, 2 (May 1984): 169. 86. John Maynard Keynes, The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes: Volume VIII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 19–23, quoted in Peden, “The ‘Treasury View,’” 170. 87. John Quiggin, Zombie Economics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012). 88. Robinson, “Second Crisis,” 1. 89. Ibid., 4.

pages: 524 words: 143,993

The Shifts and the Shocks: What We've Learned--And Have Still to Learn--From the Financial Crisis by Martin Wolf

air freight, Alan Greenspan, anti-communist, Asian financial crisis, asset allocation, asset-backed security, balance sheet recession, bank run, banking crisis, banks create money, Basel III, Bear Stearns, Ben Bernanke: helicopter money, Berlin Wall, Black Swan, bonus culture, break the buck, Bretton Woods, business cycle, call centre, capital asset pricing model, capital controls, Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty, Carmen Reinhart, central bank independence, collateralized debt obligation, corporate governance, creative destruction, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, currency manipulation / currency intervention, currency peg, currency risk, debt deflation, deglobalization, Deng Xiaoping, diversification, double entry bookkeeping, en.wikipedia.org, Erik Brynjolfsson, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, eurozone crisis, Fall of the Berlin Wall, fiat currency, financial deregulation, financial innovation, financial repression, floating exchange rates, foreign exchange controls, forward guidance, Fractional reserve banking, full employment, Glass-Steagall Act, global rebalancing, global reserve currency, Growth in a Time of Debt, Hyman Minsky, income inequality, inflation targeting, information asymmetry, invisible hand, Joseph Schumpeter, Kenneth Rogoff, labour market flexibility, labour mobility, Les Trente Glorieuses, light touch regulation, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, liquidity trap, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, mandatory minimum, margin call, market bubble, market clearing, market fragmentation, Martin Wolf, Mexican peso crisis / tequila crisis, Minsky moment, Modern Monetary Theory, Money creation, money market fund, moral hazard, mortgage debt, negative equity, new economy, North Sea oil, Northern Rock, open economy, paradox of thrift, Paul Samuelson, price stability, private sector deleveraging, proprietary trading, purchasing power parity, pushing on a string, quantitative easing, Real Time Gross Settlement, regulatory arbitrage, reserve currency, Richard Feynman, risk-adjusted returns, risk/return, road to serfdom, Robert Gordon, Robert Shiller, Ronald Reagan, savings glut, Second Machine Age, secular stagnation, shareholder value, short selling, sovereign wealth fund, special drawing rights, subprime mortgage crisis, tail risk, The Chicago School, The Great Moderation, The Market for Lemons, the market place, The Myth of the Rational Market, the payments system, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, too big to fail, Tyler Cowen, Tyler Cowen: Great Stagnation, vertical integration, very high income, winner-take-all economy, zero-sum game

The standard tools of liquidationism – depressions, mass bankruptcy and mass unemployment – are needed to deliver this outcome. The Eurozone might even be described as structurally liquidationist. It is easy to understand why people argue that one should let the medicine work, unchecked, however bad the side effects. It is, like chemotherapy, a cure that comes close to killing the patient. But this liquidationism is also tempered, in practice, making its results slower and the treatment not quite as brutal as it would otherwise be. Yet did member countries really bargain for such a ‘liquidationism light’? Might it then be possible to temper the liquidationism, while also avoiding the onerous limits on sovereign discretion of the Eurozone’s new orthodoxy?

…

The UK’s austerity programme, launched in 2010, removed fiscal support for recovery and, together with the falling output of North Sea oil, adverse shifts in the terms of trade and rising domestic prices of imports, resulted in economic stagnation for a further three years. The outcome was far worse in crisis-hit parts of the Eurozone, where the approach taken was close to liquidationism (on which see further below). In brief, the short-term record of the new orthodoxy was far from a catastrophe. But it could have done far better. In particular, it failed to provide adequate support for demand, partly because of premature fiscal tightening. A widely promoted alternative to the new orthodoxy has been ‘liquidationism’ – reliance on the free market, without fiscal or monetary policy support. This approach has limited support among academic economists, but substantial support among active participants in financial markets, including some successful speculators.

…

Moreover, rescue facilities, particularly if limited in scope, should not encourage excessive financial imprudence, because those who make bad decisions still suffer harsh penalties to their finances, their reputations, or, more often, both. Yet liquidationism is still quite correct on one thing: shareholders should never be rescued. There should also be a clear order of conversion of debt into equity in a well-defined resolution regime that allows financial institutions to continue to function. Only in extreme circumstances should a government rescue be contemplated. But, in democracies, governments will always respond to the public’s desire for basic security. Outright collapse of the core financial system cannot be permitted. If pure liquidationism is unnecessary, unworkable and unbearable, the new orthodoxy is also insufficient.

pages: 267 words: 71,123

End This Depression Now! by Paul Krugman

airline deregulation, Alan Greenspan, Asian financial crisis, asset-backed security, bank run, banking crisis, bond market vigilante , Bretton Woods, business cycle, capital asset pricing model, Carmen Reinhart, centre right, correlation does not imply causation, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, currency manipulation / currency intervention, debt deflation, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, financial deregulation, financial innovation, Financial Instability Hypothesis, full employment, German hyperinflation, Glass-Steagall Act, Gordon Gekko, high-speed rail, Hyman Minsky, income inequality, inflation targeting, invisible hand, it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it, It's morning again in America, James Carville said: "I would like to be reincarnated as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.", Joseph Schumpeter, junk bonds, Kenneth Rogoff, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, liquidity trap, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, low skilled workers, Mark Zuckerberg, Minsky moment, Money creation, money market fund, moral hazard, mortgage debt, negative equity, paradox of thrift, Paul Samuelson, price stability, quantitative easing, rent-seeking, Robert Gordon, Ronald Reagan, Savings and loan crisis, Upton Sinclair, We are all Keynesians now, We are the 99%, working poor, Works Progress Administration

When I studied economics, claims like Schumpeter’s were described as characteristic of the “liquidationist” school, which basically asserted that the suffering that takes place in a depression is good and natural, and that nothing should be done to alleviate it. And liquidationism, we were taught, had been decisively refuted by events. Never mind Keynes; Milton Friedman had crusaded against this kind of thinking. Yet in 2010 liquidationist arguments no different from those of Schumpeter (or Hayek) suddenly regained prominence. Rajan’s writings provide the most explicit statement of the new liquidationism, but I have heard similar arguments from many financial officials. No new evidence or careful reasoning was presented to explain why this doctrine should rise from the dead.

…

There are players on the political landscape—important players, with real influence—who don’t believe that it’s possible for the economy as a whole to suffer from inadequate demand. There can be lack of demand for some goods, they say, but there can’t be too little demand across the board. Why? Because, they claim, people have to spend their income on something. This is the fallacy Keynes called “Say’s Law”; it’s also sometimes called the “Treasury view,” a reference not to our Treasury but to His Majesty’s Treasury in the 1930s, an institution that insisted that any government spending would always displace an equal amount of private spending. Just so you know that I’m not describing a straw man, here’s Brian Riedl of the Heritage Foundation (a right-wing think tank) in an early-2009 interview with National Review: The grand Keynesian myth is that you can spend money and thereby increase demand.

pages: 238 words: 73,121

Does Capitalism Have a Future? by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, Craig Calhoun, Stephen Hoye, Audible Studios

affirmative action, blood diamond, Bretton Woods, BRICs, British Empire, business cycle, butterfly effect, company town, creative destruction, deindustrialization, demographic transition, Deng Xiaoping, discovery of the americas, distributed generation, Dr. Strangelove, eurozone crisis, fiat currency, financial engineering, full employment, gentrification, Gini coefficient, global village, hydraulic fracturing, income inequality, Isaac Newton, job automation, joint-stock company, Joseph Schumpeter, junk bonds, land tenure, liberal capitalism, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, loose coupling, low skilled workers, market bubble, market fundamentalism, mass immigration, means of production, mega-rich, Mikhail Gorbachev, military-industrial complex, mutually assured destruction, offshore financial centre, oil shale / tar sands, Ponzi scheme, postindustrial economy, reserve currency, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, short selling, Silicon Valley, South Sea Bubble, sovereign wealth fund, Suez crisis 1956, too big to fail, transaction costs, vertical integration, Washington Consensus, WikiLeaks

There was ideological attachment by old regimes to laissez-faire economics, a stock market bubble, and an uncompleted transition from old to new forms of manufacturing, all of which lowered the employment potential of the economy. In America, the eye of the storm, grave policy mistakes were also made by Congress and by the Federal Reserve Board rooted in the market fundamentalism of this period which reached its ghastly climax in what was called “liquidationism”–the pursuit of austerity measures in order to destroy inefficient firms, industries, investors, and workers. Absent any two or three of these varied causes cascading on top of each other and we would have been labeling this a cyclical recession. But the cascade was by no means inevitable. The Depression is often treated as being global but it struck unevenly.

…

There do seem to be economic lessons to draw from these crises which in theory might reduce the likelihood of future crises. But it is far from clear that powerful elites have drawn the appropriate lessons. Neoliberal austerity programs inflicted on economies in recession unfortunately recall the unhelpful role of liquidationism at the beginning of the 1930s. Note also that in the 20th century the two terrible wars had absolutely contrary effects, further worsening the problem of prediction. The first war helped intensify a recession into the Great Depression, the second substantially contributed to the biggest boom of all—and to American hegemony.

pages: 324 words: 93,606

No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy by Linsey McGoey

"World Economic Forum" Davos, activist fund / activist shareholder / activist investor, Affordable Care Act / Obamacare, agricultural Revolution, American Legislative Exchange Council, Bear Stearns, bitcoin, Bob Geldof, cashless society, clean water, cognitive dissonance, collapse of Lehman Brothers, colonial rule, corporate governance, corporate social responsibility, crony capitalism, effective altruism, Etonian, Evgeny Morozov, financial innovation, Food sovereignty, Ford paid five dollars a day, germ theory of disease, hiring and firing, Howard Zinn, Ida Tarbell, impact investing, income inequality, income per capita, invisible hand, Jane Jacobs, John Elkington, Joseph Schumpeter, Leo Hollis, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, M-Pesa, Mahatma Gandhi, Mark Zuckerberg, meta-analysis, Michael Milken, microcredit, Mitch Kapor, Mont Pelerin Society, Naomi Klein, Neil Armstrong, obamacare, Peter Singer: altruism, Peter Thiel, plutocrats, price mechanism, profit motive, public intellectual, Ralph Waldo Emerson, rent-seeking, road to serfdom, Ronald Reagan, school choice, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), Silicon Valley, Slavoj Žižek, Steve Jobs, strikebreaker, subprime mortgage crisis, tacit knowledge, technological solutionism, TED Talk, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thorstein Veblen, trickle-down economics, urban planning, W. E. B. Du Bois, wealth creators

Government aid, he argued, must be extended ‘not as a matter of charity but as a matter of social duty’.38 The policies of the Hoover-Mellon alliance have been much commented in recent years, as both Democrats and Republicans advance fiscal policies reminiscent of Mellon’s time in the US treasury. The economist Paul Krugman puts it bluntly: ‘Mellon-style liquidationism is now the official doctrine of the G.O.P’.39 But the recent focus on economic similarities has overshadowed attention to something less perceptible: shared ideological commitment. Like Carnegie before him and Fries today, Mellon was a firm believer in the credo that wealth concentration will inevitably foster collective benefits.

Money and Government: The Past and Future of Economics by Robert Skidelsky

"Friedman doctrine" OR "shareholder theory", Alan Greenspan, anti-globalists, Asian financial crisis, asset-backed security, bank run, banking crisis, banks create money, barriers to entry, Basel III, basic income, Bear Stearns, behavioural economics, Ben Bernanke: helicopter money, Big bang: deregulation of the City of London, book value, Bretton Woods, British Empire, business cycle, capital controls, Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty, Carmen Reinhart, central bank independence, cognitive dissonance, collapse of Lehman Brothers, collateralized debt obligation, collective bargaining, constrained optimization, Corn Laws, correlation does not imply causation, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, David Graeber, David Ricardo: comparative advantage, debt deflation, Deng Xiaoping, Donald Trump, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, eurozone crisis, fake news, financial deregulation, financial engineering, financial innovation, Financial Instability Hypothesis, forward guidance, Fractional reserve banking, full employment, Gini coefficient, Glass-Steagall Act, Goodhart's law, Growth in a Time of Debt, guns versus butter model, Hyman Minsky, income inequality, incomplete markets, inflation targeting, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, John Maynard Keynes: Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, John Maynard Keynes: technological unemployment, Joseph Schumpeter, Kenneth Rogoff, Kondratiev cycle, labour market flexibility, labour mobility, land bank, law of one price, liberal capitalism, light touch regulation, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, liquidity trap, long and variable lags, low interest rates, market clearing, market friction, Martin Wolf, means of production, Meghnad Desai, Mexican peso crisis / tequila crisis, mobile money, Modern Monetary Theory, Money creation, Mont Pelerin Society, moral hazard, mortgage debt, new economy, Nick Leeson, North Sea oil, Northern Rock, nudge theory, offshore financial centre, oil shock, open economy, paradox of thrift, Pareto efficiency, Paul Samuelson, Phillips curve, placebo effect, post-war consensus, price stability, profit maximization, proprietary trading, public intellectual, quantitative easing, random walk, regulatory arbitrage, rent-seeking, reserve currency, Richard Thaler, rising living standards, risk/return, road to serfdom, Robert Shiller, Ronald Reagan, savings glut, secular stagnation, shareholder value, short selling, Simon Kuznets, structural adjustment programs, technological determinism, The Chicago School, The Great Moderation, the payments system, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, Thorstein Veblen, tontine, too big to fail, trade liberalization, value at risk, Washington Consensus, yield curve, zero-sum game

In a deep slump it was no longer enough to manage expectations about the future of the price level; the expectations which needed managing were about the future of output and employment. This required fiscal policy. But fiscal policy to fight the slump offered its own obstacle in the form of the Treasury View, presented at the Macmillan Committee by the formidable Sir Richard Hopkins. Keynes thought he knew what the Treasury View was, and that he was in a position to refute it. The Treasury had claimed that loan-financed public spending could not add to investment and employment, only divert them from existing uses. This was true, Keynes was prepared to say, only on the assumption of full employment.

…

Peden, G. C. (1983), Sir Richard Hopkins and the ‘Keynesian Revolution’ in employment policy, 1929–1945. Economic History Review, 36 (2), pp. 281–96. Peden, G. C. (1984), The ‘Treasury View’ on public works and employment in the interwar period. Economic History Review, 37 (2), pp. 167–81. 450 Bi bl io g r a p h y Peden, G. C. (1993), The road to and from Gairloch: Lloyd George, unemployment, inflation, and the ‘Treasury View’ in 1921. Twentieth Century British History, 4 (3), pp. 224–49. Peden, G. C. (2000), The Treasury and British Public Policy, 1906–1959. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Peden, G.

…

Particularly striking was one in December 1921 by Sir Edwin Montagu, Secretary of State for India, that the government should deliberately budget for a deficit by reducing income tax, with the expectation that the borrowing requirement would decline as the tax cuts revived the economy, and therefore the government’s revenue.22 Lloyd George’s own preference was to invest in large public works programmes; these counted as capital expenditure and so would not affect the Chancellor’s budget for current spending. It was against these supposedly 107 T h e R i s e , T r i u m p h a n d Fa l l of K e y n e s improvident plans that the ‘Treasury View’ defined itself. In a note to Lloyd George’s Committee, Sir Otto Niemeyer, Controller of Finance at the Treasury, explained that unemployment was not due to insufficient demand, but excessive wage costs. ‘The earnings of British industry are not sufficient to pay the present scale of wages all round.

Drink?: The New Science of Alcohol and Your Health by David Nutt

Boris Johnson, Bullingdon Club, carbon footprint, en.wikipedia.org, epigenetics, impulse control, Kickstarter, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, microbiome, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)

Taxation of alcohol raises about £20 billion a year. That leaves a net deficit of up to £30 billion. But the government are terrified of making any change to alcohol’s status because its income from taxation is immediate. The industry pays its tax quarterly and duty is coming in constantly. The Treasury view is that if things changed, the tax income would reduce but the health benefits wouldn’t happen for 10 to 20 years. The truth is, some of the health costs are immediate. Think about an A&E department on a Friday night: if it was only half full, you wouldn’t need so many nurses and doctors. And if you can reduce someone’s consumption of cheap cider from, say, two litres a day down to one, they can then be treated more cheaply in a normal ward and not in intensive care, as they won’t be dying.

pages: 306 words: 78,893

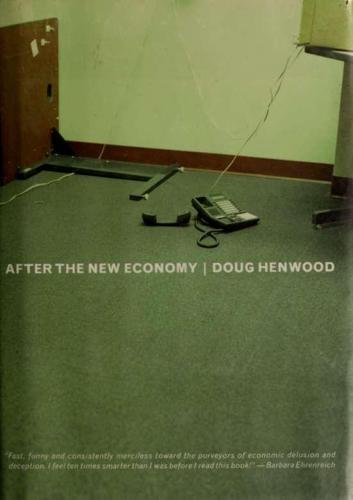

After the New Economy: The Binge . . . And the Hangover That Won't Go Away by Doug Henwood

"World Economic Forum" Davos, accounting loophole / creative accounting, affirmative action, Alan Greenspan, AOL-Time Warner, Asian financial crisis, barriers to entry, Benchmark Capital, book value, borderless world, Branko Milanovic, Bretton Woods, business cycle, California energy crisis, capital controls, corporate governance, corporate raider, correlation coefficient, credit crunch, deindustrialization, dematerialisation, deskilling, digital divide, electricity market, emotional labour, ending welfare as we know it, feminist movement, fulfillment center, full employment, gender pay gap, George Gilder, glass ceiling, Glass-Steagall Act, Gordon Gekko, government statistician, greed is good, half of the world's population has never made a phone call, income inequality, indoor plumbing, intangible asset, Internet Archive, job satisfaction, joint-stock company, Kevin Kelly, labor-force participation, Larry Ellison, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, low interest rates, manufacturing employment, Mary Meeker, means of production, Michael Milken, minimum wage unemployment, Naomi Klein, new economy, occupational segregation, PalmPilot, pets.com, post-work, profit maximization, purchasing power parity, race to the bottom, Ralph Nader, rewilding, Robert Gordon, Robert Shiller, Robert Solow, rolling blackouts, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, Silicon Valley, Simon Kuznets, statistical model, stock buybacks, structural adjustment programs, tech worker, Telecommunications Act of 1996, telemarketer, The Bell Curve by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, total factor productivity, union organizing, War on Poverty, warehouse automation, women in the workforce, working poor, zero-sum game

Many countries protected their industries and regulated finance and other sectors, cross-border capital flows were often restricted, and currencies weren't always easily convertible into other currencies.^ The nineteenth-century economics of Hght regulation, tight budgets free prices, and self-equilibrating markets—^what Keynes derided during the Depression as "the Treasury view"—seemed deeply buried. You needn't take the word of a long-dead Marxist Hke Kalecki for it, though; there's supporting testimony from Alan Greenspan. Several times Finance 207 during the late 1990s, Greenspan worried publicly that, as unemployment drifted steadily lower the "pool of available workers" was running dry.''

pages: 324 words: 90,253

When the Money Runs Out: The End of Western Affluence by Stephen D. King

Alan Greenspan, Albert Einstein, Apollo 11, Asian financial crisis, asset-backed security, banking crisis, Basel III, Bear Stearns, Berlin Wall, Bernie Madoff, bond market vigilante , British Empire, business cycle, capital controls, central bank independence, collapse of Lehman Brothers, collateralized debt obligation, congestion charging, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, crony capitalism, cross-subsidies, currency risk, debt deflation, Deng Xiaoping, Diane Coyle, endowment effect, eurozone crisis, Fall of the Berlin Wall, financial innovation, financial repression, fixed income, floating exchange rates, Ford Model T, full employment, George Akerlof, German hyperinflation, Glass-Steagall Act, Hyman Minsky, income inequality, income per capita, inflation targeting, invisible hand, John Maynard Keynes: Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, joint-stock company, junk bonds, Kickstarter, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, liquidity trap, London Interbank Offered Rate, loss aversion, low interest rates, market clearing, mass immigration, Minsky moment, moral hazard, mortgage debt, Neil Armstrong, new economy, New Urbanism, Nick Leeson, Northern Rock, Occupy movement, oil shale / tar sands, oil shock, old age dependency ratio, price mechanism, price stability, quantitative easing, railway mania, rent-seeking, reserve currency, rising living standards, risk free rate, Savings and loan crisis, seminal paper, South Sea Bubble, sovereign wealth fund, technology bubble, The Market for Lemons, The Spirit Level, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, Tobin tax, too big to fail, trade route, trickle-down economics, Washington Consensus, women in the workforce, working-age population

With draconian severity, he has set himself to balance the Budget … This is certainly an heroic achievement which should leave no doubt in the minds of our foreign creditors that at any rate we are thoroughly prepared to pay our way by living within our means … there need no longer be any fear that the pound sterling will be overwhelmed by budgetary instability.2 This extraordinary enthusiasm stood in marked contrast to the attitude towards Snowden's effort in April of that year, which the Times caustically labelled ‘A Makeshift Budget’: The taxpayer is at best in the position of the patient who has escaped for the moment the more painful attentions of the dentist, only to leave the real business of the operation until the next visit … The outstanding features of Mr Snowden's Budget … are a quite unwarranted optimism and a misplaced fertility of makeshift expedients … His deficit is due in the main to an increase in current expenditure which shows no signs of abating: nor is there any solid reason whatever for supposing that any such marked recovery as he anticipates is likely to take place during the next twelve months. However deplorable any increase in taxation may be, there is at least one thing more deplorable still, and that is increased expenditure uncovered by current revenue. Today, Snowden's Budget and the ‘Treasury View’ that underpinned it are roundly condemned. As Ed Balls, the Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, argued in 2010: ‘And the result [of Snowden's Budget]? The promised private sector recovery failed to materialise as companies themselves sought to retrench. Unemployment soared. The Great Depression soured world politics and divided societies.‘3 This is, if you like, the new conventional wisdom.

pages: 723 words: 98,951

Down the Tube: The Battle for London's Underground by Christian Wolmar

congestion charging, Crossrail, iterative process, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, megaproject, profit motive, transaction costs

In giving evidence to the transport select committee in April of that year, Denis Tunnicliffe and his fellow London Underground executives were unable to provide much detail of the contracts. Indeed, Tunnicliffe suggested that the length would probably be between fifteen and twenty-five years,* rather than the eventual thirty, and there was still uncertainty over whether there would be one, two or three infrastructure companies. That decision was not made until July when the Treasury view, which was always that there must be competition and preferably that there should be three players,* prevailed over the preference of John Prescott and London Transport for a single infrastructure company. At the time, the deadline for the contracts to be signed was envisaged to be April 2000, in time for the creation of the Greater London Authority and the mayor.

pages: 363 words: 98,024

Keeping at It: The Quest for Sound Money and Good Government by Paul Volcker, Christine Harper

Alan Greenspan, anti-communist, Ayatollah Khomeini, banking crisis, Bear Stearns, behavioural economics, Black Monday: stock market crash in 1987, Bretton Woods, business cycle, central bank independence, corporate governance, Credit Default Swap, Donald Trump, fiat currency, financial engineering, financial innovation, fixed income, floating exchange rates, forensic accounting, full employment, Glass-Steagall Act, global reserve currency, income per capita, inflation targeting, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, low interest rates, margin call, money market fund, Nixon shock, oil-for-food scandal, Paul Samuelson, price stability, proprietary trading, quantitative easing, reserve currency, Right to Buy, risk-adjusted returns, Ronald Reagan, Rosa Parks, Savings and loan crisis, secular stagnation, Sharpe ratio, Silicon Valley, special drawing rights, too big to fail, traveling salesman, urban planning

But I did play a bit part. One of my responsibilities was economic forecasting, which I had done at the New York Fed. Looking ahead with the help of longtime civil servant and practical economist Herman Liebling, I concluded we would narrowly avoid recession in 1962, contrary to the CEA’s concerns. That supported the Treasury view: don’t rush the tax bill; do it right. Slow and careful won the day. Happily for the country (and for me), we did avoid recession. The tax program the president outlined in a mid-1962 press conference, days after the worst stock market dive since 1929, looked toward extensive reform. I recall producing a lengthy analysis of the economic impact of the proposed tax program for Under Secretary Henry “Joe” Fowler.

pages: 273 words: 34,920

Free Market Missionaries: The Corporate Manipulation of Community Values by Sharon Beder

"Friedman doctrine" OR "shareholder theory", "World Economic Forum" Davos, Alan Greenspan, anti-communist, battle of ideas, business climate, Cornelius Vanderbilt, corporate governance, electricity market, en.wikipedia.org, full employment, Herbert Marcuse, Ida Tarbell, income inequality, invisible hand, junk bonds, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, minimum wage unemployment, Mont Pelerin Society, new economy, old-boy network, popular capitalism, Powell Memorandum, price mechanism, profit motive, Ralph Nader, rent control, risk/return, road to serfdom, Ronald Reagan, school vouchers, shareholder value, spread of share-ownership, structural adjustment programs, The Chicago School, the market place, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas L Friedman, Torches of Freedom, trade liberalization, traveling salesman, trickle-down economics, two and twenty, Upton Sinclair, Washington Consensus, wealth creators, young professional

By the 1990s it had been reformulated as: how can governments create competitive market situations to ensure world-best practice is pursued and international standards are achieved? 66 The shift in the ALP government approach was such that, although elected in 1983 on promises of an expanded budget ‘to increase demand and commence the arduous task of sustained economic recovery’, the Treasury view prevailed and by 1984 the prime minister was promising not to raise taxes nor increase the deficit as a proportion of GDP. In fact, over the following seven years, the deficit fell from 28.9 per cent to 23.7 per cent of GDP. Similarly, prior to the election, Labor had been critical of a proposal for deregulation of the financial sector.

pages: 372 words: 109,536

The Panama Papers: Breaking the Story of How the Rich and Powerful Hide Their Money by Frederik Obermaier

air gap, banking crisis, blood diamond, book value, credit crunch, crony capitalism, Deng Xiaoping, Edward Snowden, family office, Global Witness, high net worth, income inequality, Jeremy Corbyn, Kickstarter, Laura Poitras, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, mega-rich, megaproject, Mikhail Gorbachev, mortgage debt, Nelson Mandela, offshore financial centre, optical character recognition, out of africa, race to the bottom, vertical integration, We are the 99%, WikiLeaks

We draw up lists and compare the details in our files with information from the EU, the UN and the USA. Below is a selection. Bredenkamp, John Arnold This South African-born arms dealer was subject to EU sanctions from 2009 to 2012 due to his ‘close links to the Zimbabwean government’. The US Department of the Treasury views him as an associate of Mugabe’s regime and imposed sanctions on Bredenkamp and twenty of his firms in 2008.5 Makhlouf, Ihab Syrian president Bashar al-Assad’s cousin was sanctioned by the EU in May 2011 because he ‘funds the regime and helps to suppress demonstrations’. Makhlouf, Iyab Bashar al-Assad’s cousin and a Syrian intelligence officer was put on the EU sanctions list because he was allegedly involved in putting down protests.

pages: 494 words: 132,975

Keynes Hayek: The Clash That Defined Modern Economics by Nicholas Wapshott

airport security, Alan Greenspan, banking crisis, Bear Stearns, Bretton Woods, British Empire, business cycle, collective bargaining, complexity theory, creative destruction, cuban missile crisis, Francis Fukuyama: the end of history, full employment, Gordon Gekko, greed is good, Gunnar Myrdal, if you build it, they will come, Isaac Newton, Joseph Schumpeter, Kickstarter, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, means of production, military-industrial complex, Mont Pelerin Society, mortgage debt, New Journalism, Nixon triggered the end of the Bretton Woods system, Northern Rock, Paul Samuelson, Philip Mirowski, Phillips curve, price mechanism, public intellectual, pushing on a string, road to serfdom, Robert Bork, Robert Solow, Ronald Reagan, Simon Kuznets, The Chicago School, The Great Moderation, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, trickle-down economics, Tyler Cowen, War on Poverty, We are all Keynesians now, Yom Kippur War

Keynes and Reginald McKenna, the former wartime Liberal chancellor, argued that reducing wages by 10 percent would have to be imposed on the coal miners and that prolonged strikes and a contraction (slowing down of activity) in key industries would follow. Three days later, after persistent pressure from his more orthodox colleagues, Churchill abandoned his instinctive opposition to the Treasury view and agreed to restore fixing the pound sterling to the price of gold—“the gold standard”—at its prewar parity. Churchill’s decision led Keynes to write a series of articles for The Nation that were collected in a best-selling book, The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill, whose title echoed his Economic Consequences of the Peace.

pages: 466 words: 127,728

The Death of Money: The Coming Collapse of the International Monetary System by James Rickards

"World Economic Forum" Davos, Affordable Care Act / Obamacare, Alan Greenspan, Asian financial crisis, asset allocation, Ayatollah Khomeini, bank run, banking crisis, Bear Stearns, Ben Bernanke: helicopter money, bitcoin, Black Monday: stock market crash in 1987, Black Swan, Boeing 747, Bretton Woods, BRICs, business climate, business cycle, buy and hold, capital controls, Carmen Reinhart, central bank independence, centre right, collateralized debt obligation, collective bargaining, complexity theory, computer age, credit crunch, currency peg, David Graeber, debt deflation, Deng Xiaoping, diversification, Dr. Strangelove, Edward Snowden, eurozone crisis, fiat currency, financial engineering, financial innovation, financial intermediation, financial repression, fixed income, Flash crash, floating exchange rates, forward guidance, G4S, George Akerlof, global macro, global reserve currency, global supply chain, Goodhart's law, Growth in a Time of Debt, guns versus butter model, Herman Kahn, high-speed rail, income inequality, inflation targeting, information asymmetry, invisible hand, jitney, John Meriwether, junk bonds, Kenneth Rogoff, labor-force participation, Lao Tzu, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, liquidity trap, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, mandelbrot fractal, margin call, market bubble, market clearing, market design, megaproject, Modern Monetary Theory, Money creation, money market fund, money: store of value / unit of account / medium of exchange, mutually assured destruction, Nixon triggered the end of the Bretton Woods system, obamacare, offshore financial centre, oil shale / tar sands, open economy, operational security, plutocrats, Ponzi scheme, power law, price stability, public intellectual, quantitative easing, RAND corporation, reserve currency, risk-adjusted returns, Rod Stewart played at Stephen Schwarzman birthday party, Ronald Reagan, Satoshi Nakamoto, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley startup, Skype, Solyndra, sovereign wealth fund, special drawing rights, Stuxnet, The Market for Lemons, Thomas Kuhn: the structure of scientific revolutions, Thomas L Friedman, too big to fail, trade route, undersea cable, uranium enrichment, Washington Consensus, working-age population, yield curve

Treasury and Federal Reserve routinely pour cold water on the threat analysis. Their rejoinder begins with estimates of the market impact of financial war, then concludes that the Chinese or other major powers would never engage in it because it would produce massive losses on their own portfolios. This view reflects a dangerous official naïveté. The Treasury view supposes that the purpose of financial war is financial gain. It is not. The purpose of financial war is to degrade an enemy’s capabilities and subdue the enemy while seeking geopolitical advantage in targeted areas. Making a portfolio profit has nothing to do with a financial attack. If the attacker can bring an opponent to a state of near collapse and paralysis through a financial catastrophe while advancing on other fronts, then the financial war will be judged a success, even if the attacker incurs large costs.

pages: 586 words: 159,901

Wall Street: How It Works And for Whom by Doug Henwood

accounting loophole / creative accounting, activist fund / activist shareholder / activist investor, affirmative action, Alan Greenspan, Andrei Shleifer, asset allocation, asset-backed security, bank run, banking crisis, barriers to entry, bond market vigilante , book value, borderless world, Bretton Woods, British Empire, business cycle, buy the rumour, sell the news, capital asset pricing model, capital controls, Carl Icahn, central bank independence, computerized trading, corporate governance, corporate raider, correlation coefficient, correlation does not imply causation, credit crunch, currency manipulation / currency intervention, currency risk, David Ricardo: comparative advantage, debt deflation, declining real wages, deindustrialization, dematerialisation, disinformation, diversification, diversified portfolio, Donald Trump, equity premium, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, experimental subject, facts on the ground, financial deregulation, financial engineering, financial innovation, Financial Instability Hypothesis, floating exchange rates, full employment, George Akerlof, George Gilder, Glass-Steagall Act, hiring and firing, Hyman Minsky, implied volatility, index arbitrage, index fund, information asymmetry, interest rate swap, Internet Archive, invisible hand, Irwin Jacobs, Isaac Newton, joint-stock company, Joseph Schumpeter, junk bonds, kremlinology, labor-force participation, late capitalism, law of one price, liberal capitalism, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, London Interbank Offered Rate, long and variable lags, Louis Bachelier, low interest rates, market bubble, Mexican peso crisis / tequila crisis, Michael Milken, microcredit, minimum wage unemployment, money market fund, moral hazard, mortgage debt, mortgage tax deduction, Myron Scholes, oil shock, Paul Samuelson, payday loans, pension reform, planned obsolescence, plutocrats, Post-Keynesian economics, price mechanism, price stability, prisoner's dilemma, profit maximization, proprietary trading, publication bias, Ralph Nader, random walk, reserve currency, Richard Thaler, risk tolerance, Robert Gordon, Robert Shiller, Savings and loan crisis, selection bias, shareholder value, short selling, Slavoj Žižek, South Sea Bubble, stock buybacks, The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, The Market for Lemons, The Nature of the Firm, The Predators' Ball, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, transaction costs, transcontinental railway, women in the workforce, yield curve, zero-coupon bond

As the collapse unfolded, Hilferding again advocated austerity — budget cuts and tax increases, while resisting ail "inflationary" schemes (Darity and Horn 1985). While Hilferding obviously can't be blamed for the collapse, his loyalty to capitalist financial orthodoxy — what Keynes derided in Britain as "the Treasury view" — is inexcusable in a socialist, and further proof that in practical matters, Marxians can be as blinkered as the most austere Chicagoan. money and power Several aspects of Marx's theorizing on money and credit are worth savoring: the inseparability of money and commerce, the political nature of money (and the inseparability of market and state), and the role of credit in breaking capital's own barriers to accumulation.

pages: 566 words: 160,453

Not Working: Where Have All the Good Jobs Gone? by David G. Blanchflower

90 percent rule, active measures, affirmative action, Affordable Care Act / Obamacare, Albert Einstein, bank run, banking crisis, basic income, Bear Stearns, behavioural economics, Berlin Wall, Bernie Madoff, Bernie Sanders, Black Lives Matter, Black Swan, Boris Johnson, Brexit referendum, business cycle, Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty, Carmen Reinhart, Clapham omnibus, collective bargaining, correlation does not imply causation, credit crunch, declining real wages, deindustrialization, Donald Trump, driverless car, estate planning, fake news, Fall of the Berlin Wall, full employment, George Akerlof, gig economy, Gini coefficient, Growth in a Time of Debt, high-speed rail, illegal immigration, income inequality, independent contractor, indoor plumbing, inflation targeting, Jeremy Corbyn, job satisfaction, John Bercow, Kenneth Rogoff, labor-force participation, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, longitudinal study, low interest rates, low skilled workers, manufacturing employment, Mark Zuckerberg, market clearing, Martin Wolf, mass incarceration, meta-analysis, moral hazard, Nate Silver, negative equity, new economy, Northern Rock, obamacare, oil shock, open borders, opioid epidemic / opioid crisis, Own Your Own Home, p-value, Panamax, pension reform, Phillips curve, plutocrats, post-materialism, price stability, prisoner's dilemma, quantitative easing, rent control, Richard Thaler, Robert Shiller, Ronald Coase, selection bias, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), Silicon Valley, South Sea Bubble, The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen, Thorstein Veblen, trade liberalization, universal basic income, University of East Anglia, urban planning, working poor, working-age population, yield curve

Figure 11.4. “The feller ought to be ashamed! Encouraging rain!” This is a famous cartoon by David Low printed in the UK Evening Standard on January 5, 1938, depicting the residences of the UK prime minister at #10 Downing Street and of the Chancellor of the Exchequer at #11. As background, the Treasury view was that fiscal policy had no effect on the total amount of economic activity and unemployment, even during times of economic recession. This view was most famously advanced in the 1930s by the staff of the British Chancellor of the Exchequer. In 2010 the UK Chancellor George Osborne implemented huge public spending cuts that he argued would result in an expansionary fiscal contraction but resulted in the slowest peacetime recovery in three hundred years since the South Sea Bubble.

The Empire Project: The Rise and Fall of the British World-System, 1830–1970 by John Darwin

anti-communist, banking crisis, Bretton Woods, British Empire, capital controls, classic study, cognitive bias, colonial rule, Corn Laws, disinformation, European colonialism, floating exchange rates, full employment, imperial preference, Joseph Schumpeter, Khartoum Gordon, Kickstarter, labour mobility, land tenure, liberal capitalism, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, Mahatma Gandhi, Monroe Doctrine, new economy, New Urbanism, open economy, railway mania, reserve currency, Right to Buy, rising living standards, scientific management, Scientific racism, South China Sea, Suez canal 1869, Suez crisis 1956, tacit knowledge, the market place, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, trade route, transaction costs, transcontinental railway, undersea cable

Pretoria caved in and agreed to the exchange of its gold for sterling.75 In the colonial economies, London could set the price that was paid for their commodity exports, and restrict the manufactures they were sent in return. This was a way of exporting Britain's austerity, and reducing colonial consumption to hoard ‘British’ dollars. In the Treasury's view, selling on colonial produce was a far more promising way of increasing London's dollar income than closer relations with the Western European countries.76 Meanwhile, in a world starved of industrial goods, and with most of their pre-war competitors in disarray, the British could sell abroad all they could make.

pages: 1,744 words: 458,385

The Defence of the Realm by Christopher Andrew

Able Archer 83, active measures, anti-communist, Ayatollah Khomeini, Berlin Wall, Bletchley Park, Boeing 747, British Empire, classic study, Clive Stafford Smith, collective bargaining, credit crunch, cuban missile crisis, Desert Island Discs, disinformation, Etonian, Fall of the Berlin Wall, false flag, G4S, glass ceiling, illegal immigration, information security, job satisfaction, large denomination, liquidationism / Banker’s doctrine / the Treasury view, Mahatma Gandhi, Mikhail Gorbachev, Neil Kinnock, North Sea oil, operational security, post-work, Red Clydeside, Robert Hanssen: Double agent, Ronald Reagan, sexual politics, strikebreaker, Suez crisis 1956, Torches of Freedom, traveling salesman, union organizing, uranium enrichment, Vladimir Vetrov: Farewell Dossier, Winter of Discontent, work culture

This transposing of the sexes, and the use of other homosexual slang, at times made for difficulties of interpretation.’113 The Security Service, however, saw no reason to follow the Canadian example: ‘It was concluded that the present criterion was right, i.e. that homosexuality raises a presumption of unfitness to hold a P.V. post but the presumption can be disregarded by the Head of the Department if he is satisfied in all the circumstances that this can be done without prejudice to national security.’ In 1965 the Security Service successfully resisted the Treasury view that it might be necessary to treat homosexuality as an absolute bar against holding any post which required positive vetting.114 Though its criteria were never fully spelt out, the Service seems to have been relatively unconcerned during positive vetting by the presence of gays in the government service, provided that they did not actually identify themselves as homosexual and remained discreet about their sexual liaisons (which, until 1967, remained illegal).