Everybody Ought to Be Rich

12 results back to index

pages: 517 words: 139,477

Stocks for the Long Run 5/E: the Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long-Term Investment Strategies by Jeremy Siegel

Alan Greenspan, AOL-Time Warner, Asian financial crisis, asset allocation, backtesting, banking crisis, Bear Stearns, behavioural economics, Black Monday: stock market crash in 1987, Black-Scholes formula, book value, break the buck, Bretton Woods, business cycle, buy and hold, buy low sell high, California gold rush, capital asset pricing model, carried interest, central bank independence, cognitive dissonance, compound rate of return, computer age, computerized trading, corporate governance, correlation coefficient, Credit Default Swap, currency risk, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, Deng Xiaoping, discounted cash flows, diversification, diversified portfolio, dividend-yielding stocks, dogs of the Dow, equity premium, equity risk premium, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, eurozone crisis, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, Financial Instability Hypothesis, fixed income, Flash crash, forward guidance, fundamental attribution error, Glass-Steagall Act, housing crisis, Hyman Minsky, implied volatility, income inequality, index arbitrage, index fund, indoor plumbing, inflation targeting, invention of the printing press, Isaac Newton, it's over 9,000, John Bogle, joint-stock company, London Interbank Offered Rate, Long Term Capital Management, loss aversion, machine readable, market bubble, mental accounting, Minsky moment, Money creation, money market fund, mortgage debt, Myron Scholes, new economy, Northern Rock, oil shock, passive investing, Paul Samuelson, Peter Thiel, Ponzi scheme, prediction markets, price anchoring, price stability, proprietary trading, purchasing power parity, quantitative easing, random walk, Richard Thaler, risk free rate, risk tolerance, risk/return, Robert Gordon, Robert Shiller, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, short selling, Silicon Valley, South Sea Bubble, sovereign wealth fund, stocks for the long run, survivorship bias, technology bubble, The Great Moderation, the payments system, The Wisdom of Crowds, transaction costs, tulip mania, Tyler Cowen, Tyler Cowen: Great Stagnation, uptick rule, Vanguard fund

—ROGER LOWENSTEIN, “A COMMON MARKET: THE PUBLIC’S ZEAL TO INVEST”2 Stocks for the Long Run by Siegel? Yeah, all it’s good for now is a doorstop. —INVESTOR CALLING INTO CNBC, MARCH, 20093 “EVERYBODY OUGHT TO BE RICH” In the summer of 1929, a journalist named Samuel Crowther interviewed John J. Raskob, a senior financial executive at General Motors, about how the typical individual could build wealth by investing in stocks. In August of that year, Crowther published Raskob’s ideas in a Ladies’ Home Journal article with the audacious title “Everybody Ought to Be Rich.” In the interview, Raskob claimed that America was on the verge of a tremendous industrial expansion. He maintained that by putting just $15 per month into good common stocks, investors could expect their wealth to grow steadily to $80,000 over the next 20 years.

…

This limitation of liability shall apply to any claim or cause whatsoever whether such claim or cause arises in contract, tort or otherwise. CONTENTS Foreword Preface Acknowledgments PART I STOCK RETURNS: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE Chapter 1 The Case for Equity Historical Facts and Media Fiction “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” Asset Returns Since 1802 Historical Perspectives on Stocks as Investments The Influence of Smith’s Work Common Stock Theory of Investment The Market Peak Irving Fisher’s “Permanently High Plateau” A Radical Shift in Sentiment The Postcrash View of Stock Returns The Great Bull Market of 1982-2000 Warnings of Overvaluation The Late Stage of the Great Bull Market, 1997-2000 The Top of the Market The Tech Bubble Bursts Rumblings of the Financial Crisis Beginning of the End for Lehman Brothers Chapter 2 The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 Its Origins, Impact, and Legacy The Week That Rocked World Markets Could the Great Depression Happen Again?

…

See also United Kingdom, 209–210 Entitlement crisis age wave in, 58–59, 62–64 conclusions about, 71 emerging economies and, 58–59, 64–68 introduction to, 57–58 life expectancies in, 59 productivity growth in, 69–71 retirement ages in, 59–62, 64–67 world demographics and, 62–64 Equity since 1802, generally, 5–7 during 1982–2000, 12–17 common stock theory and, 8–9 “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” on, 3–5 favorable factors for, 139 financial crises and, 17–19 Fisher on, 9 globally, 196 historical facts about, 3–19 Lehman Brothers and, 18–19 market peaks and, 9 media fiction about, 3–19 mutual funds, 358–363 overvaluation and, 14–15 “permanently high plateau” of, 9–10 in postcrash views, 11–12 premiums, 87–88 real return on, 170 required return on, 144, 147–148 risk premiums, 171–172, 350–352 sentiments about, 10–11 Smith on, 8 stocks and, historically, 7–10 tech bubble and, 16–17 top of the market and, 16 worldwide, 88–90 Equity mutual funds, 358–363 “The Equity Premium: A Puzzle,” 171 Equity risk premiums, 171–172, 350–352 Establishment surveys, 261–262 ETFs (Exchange-traded funds).

Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition: The Definitive Guide to Financial Market Returns & Long Term Investment Strategies by Jeremy J. Siegel

addicted to oil, Alan Greenspan, asset allocation, backtesting, behavioural economics, Black-Scholes formula, book value, Bretton Woods, business cycle, buy and hold, buy low sell high, California gold rush, capital asset pricing model, cognitive dissonance, compound rate of return, correlation coefficient, currency risk, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, diversification, diversified portfolio, dividend-yielding stocks, dogs of the Dow, equity premium, equity risk premium, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, fixed income, German hyperinflation, implied volatility, index arbitrage, index fund, Isaac Newton, it's over 9,000, John Bogle, joint-stock company, Long Term Capital Management, loss aversion, machine readable, market bubble, mental accounting, Money creation, Myron Scholes, new economy, oil shock, passive investing, Paul Samuelson, popular capitalism, prediction markets, price anchoring, price stability, proprietary trading, purchasing power parity, random walk, Richard Thaler, risk free rate, risk tolerance, risk/return, Robert Shiller, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, short selling, South Sea Bubble, stock buybacks, stocks for the long run, subprime mortgage crisis, survivorship bias, technology bubble, The Great Moderation, The Wisdom of Crowds, transaction costs, tulip mania, uptick rule, Vanguard fund, vertical integration

This page intentionally left blank 1 CHAPTER STOCK AND BOND RETURNS SINCE 1802 I know of no way of judging the future but by the past. PA T R I C K H E N R Y, 1 7 7 5 1 “EVERYBODY OUGHT TO BE RICH” In the summer of 1929, a journalist named Samuel Crowther interviewed John J. Raskob, a senior financial executive at General Motors, about how the typical individual could build wealth by investing in stocks. In August of that year, Crowther published Raskob’s ideas in a Ladies’ Home Journal article with the audacious title “Everybody Ought to Be Rich.” In the interview, Raskob claimed that America was on the verge of a tremendous industrial expansion. He maintained that by putting just $15 per month into good common stocks, investors could expect their wealth to grow steadily to $80,000 over the next 20 years.

…

If you’d like more information about this book, its author, or related books and websites, please click here. For more information about this title, click here C O N T E N T S Foreword xv Preface xvii Acknowledgments xxi PART 1 THE VERDICT OF HISTORY Chapter 1 Stock and Bond Returns Since 1802 3 “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” 3 Financial Market Returns from 1802 5 The Long-Term Performance of Bonds 7 The End of the Gold Standard and Price Stability 9 Total Real Returns 11 Interpretation of Returns 12 Long-Term Returns 12 Short-Term Returns and Volatility 14 Real Returns on Fixed-Income Assets 14 The Fall in Fixed-Income Returns 15 The Equity Premium 16 Worldwide Equity and Bond Returns: Global Stocks for the Long Run 18 Conclusion: Stocks for the Long Run 20 Appendix 1: Stocks from 1802 to 1870 21 Appendix 2: Arithmetic and Geometric Returns 22 v vi Chapter 2 Risk, Return, and Portfolio Allocation: Why Stocks Are Less Risky Than Bonds in the Long Run 23 Measuring Risk and Return 23 Risk and Holding Period 24 Investor Returns from Market Peaks 27 Standard Measures of Risk 28 Varying Correlation between Stock and Bond Returns 30 Efficient Frontiers 32 Recommended Portfolio Allocations 34 Inflation-Indexed Bonds 35 Conclusion 36 Chapter 3 Stock Indexes: Proxies for the Market 37 Market Averages 37 The Dow Jones Averages 38 Computation of the Dow Index 39 Long-Term Trends in the Dow Jones 40 Beware the Use of Trend Lines to Predict Future Returns 41 Value-Weighted Indexes 42 Standard & Poor’s Index 42 Nasdaq Index 43 Other Stock Indexes: The Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) 45 Return Biases in Stock Indexes 46 Appendix: What Happened to the Original 12 Dow Industrials?

…

., 156 Emerging markets: market bubble in, 166–167 sector allocation and, 175i, 177 Emotion, coping with, 363 Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA), 143–144 Employee stock options, controversy over, 104–105 Employment cost index (ECI), 246 Employment costs, 246 Employment report, 241–243 Employment statistics, 237–238 Enel, 177 Energy sector: in GICS, 53 global shares in, 175i, 177 England, end of gold standard in, 187–188 ENI, 177 Enron, 89, 234–235 Equity, world, 162, 163i, 164 Equity risk premium, 16–18, 17i, 332–333 Establishment survey, 241 Index Europe: global market share of, 179, 179i, 180i sector allocation and, 175i, 177 Evans, Richard E., 356 “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” (Crowther), 3 Excess returns, 215 Excessive trading, 325–328 Exchange-rate policies, stock market crash of 1987 and, 274–275 Exchange-traded funds (ETFs), 252–253, 258, 342 authorized participants and, 252 choosing, 262–264, 263i creating, 258 creation units and, 252 cubes, 252 diamonds, 252 exchanges in kind and, 253 spiders, 252 using, 261–262 Exchanges in kind, 253 Exelon Corp., 177 Extraordinary Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (Mackay), 324 Exxon, 55 Exxon Mobil, 40, 144, 176i, 177–178, 183 Fads, 323–325 Fama, Eugene, 140–141, 152, 157 Fannie Mae, 54, 116 “Fear and Greed” (Shulman), 86 Fed model, 113–115, 114i Federal funds market, 196 Federal funds rate, 196 Federal Reserve System (Fed): dollar stabilization program and, 274 establishment of, 191–192 Great Depression and, 79 interest rates and, 196, 197i, 198–199 371 Federal Reserve System (Fed) (Cont.): money creation and, 195–196 postdevaluation monetary policy and, 193–194 postgold monetary policy and, 194–195 rate cuts following 1998 fall on DJIA, 88 Fernandez, Henry, 356n Fidelity Magellan Fund, 345–346, 348 Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), 102–103 Financial Analysts Journal, 97 Financial markets: central bank policy and, 247 inflation’s impact on, 246 Financial sector: in GICS, 53 global shares in, 175, 175i Firestone, 64 First National Bank of Pennsylvania, 21n First Union Bank, 21n Fischhoff, B., 326n Fisher, Irving, 4n, 23q, 78–79, 79, 80, 86, 201n Fisher, Lawrence, 45, 84 Fisher effect, 201–202 Fixed-income assets: fall in returns on, 15–16 real returns on, 14–16, 15i (See also Bonds) Flintkote, 60i, 62–63, 64 Float-adjusted shares, in capitalization-weighted indexing, 353 Foman, Robert, 85 Ford, Gerald, 216 Ford Motor Company, 64 Foreign exchange risk, hedging, 173 Foreign markets (see Global investing) Fortune Brands, 48, 61, 61n Forward-looking bias, 330 Franklin, Benjamin, 65q Franklin Templeton, 346 Freddie Mac, 54, 116 French, Ken, 140–141, 152, 157 Friedman, Robert, 108n Froot, Kenneth A., 173n FT-SE index, 238 Fund performance, 342–346, 343i–345i Fundamental analysis (see Technical analysis) “Fundamental Indexation” (Arnott, Hsu, and Moore), 356 Fundamentally weighted indexation, 353–357 capitalization-weighted indexing versus, 353–355 history of, 356–357 Fundamentals, 110 Futures contracts (see Stock index futures) Gaps, 275–276 Gartley, H.

pages: 420 words: 94,064

The Revolution That Wasn't: GameStop, Reddit, and the Fleecing of Small Investors by Spencer Jakab

4chan, activist fund / activist shareholder / activist investor, barriers to entry, behavioural economics, Bernie Madoff, Bernie Sanders, Big Tech, bitcoin, Black Swan, book value, buy and hold, classic study, cloud computing, coronavirus, COVID-19, crowdsourcing, cryptocurrency, data science, deal flow, democratizing finance, diversified portfolio, Dogecoin, Donald Trump, Elon Musk, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, fake news, family office, financial innovation, gamification, global macro, global pandemic, Google Glasses, Google Hangouts, Gordon Gekko, Hacker News, income inequality, index fund, invisible hand, Jeff Bezos, Jim Simons, John Bogle, lockdown, Long Term Capital Management, loss aversion, Marc Andreessen, margin call, Mark Zuckerberg, market bubble, Masayoshi Son, meme stock, Menlo Park, move fast and break things, Myron Scholes, PalmPilot, passive investing, payment for order flow, Pershing Square Capital Management, pets.com, plutocrats, profit maximization, profit motive, race to the bottom, random walk, Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, Renaissance Technologies, Richard Thaler, ride hailing / ride sharing, risk tolerance, road to serfdom, Robinhood: mobile stock trading app, Saturday Night Live, short selling, short squeeze, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley billionaire, SoftBank, Steve Jobs, TikTok, Tony Hsieh, trickle-down economics, Vanguard fund, Vision Fund, WeWork, zero-sum game

“A man with a million dollars used to be considered rich, but so many people have at least that much in these days, or are earning incomes in excess of a normal return from a million dollars, that a millionaire does not cause any comment.” The slightly archaic turn of phrase, though not the view of a million dollars being chump change, might have tipped you off to this quote’s vintage. It was from an interview with the auto executive and stock market speculator John J. Raskob in Ladies’ Home Journal, titled “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” that hit newsstands one week before the peak of the Roaring Twenties bull market and two months before the Great Crash of 1929.[1] The American public was already deeply, fatefully in love with the stock market by then, but Raskob, who had started several investment trusts over the years, was suggesting a way for people to supercharge their participation and do some catching up with the leisure class.

…

BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 2 Interview with Jordan Belfort via Zoom video, February 11, 2021. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 3 Elon Musk (@elonmusk), “Gamestonk!!” Twitter, January 26, 2021, 4:08 p.m., twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1354174279894642703. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 4 Chapter 15: The Influencers John J. Raskob, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” Ladies Home Journal, August 1929. BACK TO NOTE REFERENCE 1 Chamath Palihapitiya (@chamath), “Lots of $GME talk soooooo. . . . We bought Feb $115 calls on $GME this morning. Let’s gooooooo!!!!!!!!” Twitter, January 26, 2021, 10:32 a.m., twitter.com/chamath/status/1354089928313823232.

pages: 319 words: 106,772

Irrational Exuberance: With a New Preface by the Author by Robert J. Shiller

Alan Greenspan, Andrei Shleifer, asset allocation, banking crisis, benefit corporation, Benoit Mandelbrot, book value, business cycle, buy and hold, computer age, correlation does not imply causation, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, demographic transition, diversification, diversified portfolio, equity premium, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, experimental subject, hindsight bias, income per capita, index fund, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Joseph Schumpeter, Long Term Capital Management, loss aversion, Mahbub ul Haq, mandelbrot fractal, market bubble, market design, market fundamentalism, Mexican peso crisis / tequila crisis, Milgram experiment, money market fund, moral hazard, new economy, open economy, pattern recognition, Phillips curve, Ponzi scheme, price anchoring, random walk, Richard Thaler, risk tolerance, Robert Shiller, Ronald Reagan, Small Order Execution System, spice trade, statistical model, stocks for the long run, Suez crisis 1956, survivorship bias, the market place, Tobin tax, transaction costs, tulip mania, uptick rule, urban decay, Y2K

“If she saved only 10% of her income and invested the savings in an S&P index fund she’d have a net worth of $1.4 million on retirement at age 67, in today’s dollars.”8 These calculations assume that the S&P index fund earns a riskless 8% real (inflation-corrected) return. There is no mention of the possibility that the return might not be so high over time, and that she might not end up a millionaire. An article with a very similar title, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” appeared in the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1929.9 It performed some very similar calculations, yet similarly omitted to describe the possibility that anything could go wrong in the long term. The article became notorious after the 1929 crash. These seemingly convincing discussions of potential increases in the stock market are rarely offered in the abstract, but instead in the context of stories about successful or unsuccessful investors, and often with an undertone suggesting the moral superiority of those who invested well.

…

Frederick Lewis Allen, Only Yesterday (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1931), p. 309. 7. David Elias, Dow 40,000: Strategies for Profiting from the Greatest Bull Market in History (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999), p. 8. 8. Dwight R. Lee and Richard B. MacKenzie, “How to (Really) Get Rich in America,” USA Weekend, August 13–15, 1999, p. 6. 9. Samuel Crowther, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich: An Interview with John J. Raskob,” Ladies Home Journal, August 1929, pp. 9, 36. 10. Bodo Schäfer, Der Weg zur finanziellen Freiheit: In sieben Jahren die erste Million (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 1999); Bernd Niquet, Keine Angst vorm nächsten Crash: Warum Aktien als Langfristanlage unschlagbar sind (Frankfurt: Campus Verlag, 1999). 11.

pages: 244 words: 58,247

The Gone Fishin' Portfolio: Get Wise, Get Wealthy...and Get on With Your Life by Alexander Green

Alan Greenspan, Albert Einstein, asset allocation, asset-backed security, backtesting, behavioural economics, borderless world, buy and hold, buy low sell high, cognitive dissonance, diversification, diversified portfolio, Elliott wave, endowment effect, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, financial independence, fixed income, framing effect, hedonic treadmill, high net worth, hindsight bias, impulse control, index fund, interest rate swap, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, John Bogle, junk bonds, Long Term Capital Management, means of production, mental accounting, Michael Milken, money market fund, Paul Samuelson, Ponzi scheme, risk tolerance, risk-adjusted returns, short selling, statistical model, stocks for the long run, sunk-cost fallacy, transaction costs, Vanguard fund, yield curve

Jeremy Siegel has told the infamous story of John Jacob Raskob. In the summer of 1929, Ladies Home Journal interviewed Raskob, a senior executive with General Motors, about how the typical individual could build wealth by investing in stocks. In the article published that August, titled “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” Raskob claimed that by putting $15 a month into high-quality stocks, even the average worker could become wealthy. His timing left something to be desired. Just seven weeks after the article appeared came Black Friday, the stock market crash of 1929. And it wasn’t until July 8, 1932, that the carnage finally came to an end.

pages: 319 words: 64,307

The Great Crash 1929 by John Kenneth Galbraith

Alan Greenspan, Bernie Madoff, business cycle, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, Ford Model T, full employment, Glass-Steagall Act, housing crisis, invention of the wheel, joint-stock company, low interest rates, margin call, market fundamentalism, short selling, South Sea Bubble, the market place

As Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, he was also politically committed to a firm friendship for the people. He believed that everyone should be in on the kind of opportunities he himself enjoyed. One of the fruits of this generous impulse during the year was an article in the Ladies' Home Journal with the attractive title, "Everybody Ought to be Rich." In it Mr. Raskob pointed out that anyone who saved fifteen dollars a month, invested it in sound common stocks, and spent no dividends would be worth—as it then appeared—some eighty thousand dollars after twenty years. Obviously, at this rate, a great many people could be rich. But there was the twenty-year delay.

pages: 223 words: 10,010

The Cost of Inequality: Why Economic Equality Is Essential for Recovery by Stewart Lansley

"World Economic Forum" Davos, Adam Curtis, air traffic controllers' union, Alan Greenspan, AOL-Time Warner, banking crisis, Basel III, Big bang: deregulation of the City of London, Bonfire of the Vanities, borderless world, Branko Milanovic, Bretton Woods, British Empire, business cycle, business process, call centre, capital controls, collective bargaining, corporate governance, corporate raider, correlation does not imply causation, creative destruction, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, crony capitalism, David Ricardo: comparative advantage, deindustrialization, Edward Glaeser, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, falling living standards, financial deregulation, financial engineering, financial innovation, Financial Instability Hypothesis, floating exchange rates, full employment, Goldman Sachs: Vampire Squid, high net worth, hiring and firing, Hyman Minsky, income inequality, James Dyson, Jeff Bezos, job automation, job polarisation, John Meriwether, Joseph Schumpeter, Kenneth Rogoff, knowledge economy, laissez-faire capitalism, Larry Ellison, light touch regulation, Londongrad, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, low skilled workers, manufacturing employment, market bubble, Martin Wolf, Mary Meeker, mittelstand, mobile money, Mont Pelerin Society, Myron Scholes, new economy, Nick Leeson, North Sea oil, Northern Rock, offshore financial centre, oil shock, plutocrats, Plutonomy: Buying Luxury, Explaining Global Imbalances, proprietary trading, Right to Buy, rising living standards, Robert Shiller, Robert Solow, Ronald Reagan, savings glut, shareholder value, The Great Moderation, The Spirit Level, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, too big to fail, Tyler Cowen, Tyler Cowen: Great Stagnation, Washington Consensus, Winter of Discontent, working-age population

In one advertisement backing Herbert Hoover during the 1928 Presidential campaign, the Republicans promised: ‘A chicken in every pot and a car in every garage’. Irving Fisher, one of the country’s most distinguished economists, opined shortly before the crash that shares had reached ‘a permanently high plateau’. On the eve of the crash the financier John J Raskob, in an article called ‘Everybody Ought to be Rich’, came out with a plan to allow the poor to make money on the stockmarket. How debt levels and income concentration soared in 1920s America (Figure 8.1) 314 As in the decade leading to 2007, much of the apparent economic miracle of the 1920s had been built on an expansion of debt. As shown in figure 8.1, the ratio of household debt to national income rose by more than 70 per cent between 1920 and 1930.

pages: 303 words: 84,023

Heads I Win, Tails I Win by Spencer Jakab

Alan Greenspan, Asian financial crisis, asset allocation, backtesting, Bear Stearns, behavioural economics, Black Monday: stock market crash in 1987, book value, business cycle, buy and hold, collapse of Lehman Brothers, correlation coefficient, crowdsourcing, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, diversification, dividend-yielding stocks, dogs of the Dow, Elliott wave, equity risk premium, estate planning, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, eurozone crisis, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, fear index, fixed income, geopolitical risk, government statistician, index fund, Isaac Newton, John Bogle, John Meriwether, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, Market Wizards by Jack D. Schwager, Mexican peso crisis / tequila crisis, money market fund, Myron Scholes, PalmPilot, passive investing, Paul Samuelson, pets.com, price anchoring, proprietary trading, Ralph Nelson Elliott, random walk, Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, risk tolerance, risk-adjusted returns, Robert Shiller, robo advisor, Savings and loan crisis, Sharpe ratio, short selling, Silicon Valley, South Sea Bubble, statistical model, Steve Jobs, subprime mortgage crisis, survivorship bias, technology bubble, transaction costs, two and twenty, VA Linux, Vanguard fund, zero-coupon bond, zero-sum game

At the other extreme was Time’s “Home $weet Home” cover in the summer of 2005 asking, “Will your home make you rich?” just months before the peak in real estate prices. Most egregious was a sensational article in Ladies’ Home Journal on the eve of the 1929 stock market crash by speculator John J. Raskob. “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” actually suggested buying stocks on margin—a strategy that financially wiped out anyone who tried it. Bestselling books mirror the same crazy swings. For example, the peak in technology stocks in 2000 was preceded by titles including Dow 36,000: The New Strategy for Profiting from the Coming Rise in the Stock Market; Dow 40,000: Strategies for Profiting from the Greatest Bull Market in History; and, hey, why not, Dow 100,000: Fact or Fiction.

pages: 309 words: 91,581

The Great Divergence: America's Growing Inequality Crisis and What We Can Do About It by Timothy Noah

air traffic controllers' union, Alan Greenspan, assortative mating, autonomous vehicles, Bear Stearns, blue-collar work, Bonfire of the Vanities, Branko Milanovic, business cycle, call centre, carbon tax, collective bargaining, compensation consultant, computer age, corporate governance, Credit Default Swap, David Ricardo: comparative advantage, Deng Xiaoping, easy for humans, difficult for computers, Erik Brynjolfsson, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, feminist movement, Ford Model T, Frank Levy and Richard Murnane: The New Division of Labor, Gini coefficient, government statistician, Gunnar Myrdal, income inequality, independent contractor, industrial robot, invisible hand, It's morning again in America, job automation, Joseph Schumpeter, longitudinal study, low skilled workers, lump of labour, manufacturing employment, moral hazard, oil shock, pattern recognition, Paul Samuelson, performance metric, positional goods, post-industrial society, postindustrial economy, proprietary trading, purchasing power parity, refrigerator car, rent control, Richard Feynman, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, Silicon Valley, Simon Kuznets, Stephen Hawking, Steve Jobs, subprime mortgage crisis, The Spirit Level, too big to fail, trickle-down economics, Tyler Cowen, Tyler Cowen: Great Stagnation, union organizing, upwardly mobile, very high income, Vilfredo Pareto, War on Poverty, We are the 99%, women in the workforce, Works Progress Administration, Yom Kippur War

To embrace the fantasy of a poverty-free America, one had to be unaware that during the 1920s the bottom 95 percent saw its proportion of the nation’s income drop from 72 percent to 64 percent.13 The bigger problem, of course, was that economic catastrophe loomed for just about everyone. Why did people believe otherwise? Partly because financial experts told them to. In August 1929 the investor and Democratic National Committee chairman John J. Raskob published, in the Ladies’ Home Journal, an article titled “Everybody Ought to be Rich.” In mid-October Yale’s Irving Fisher—the most eminent economist of the era—pronounced, “Stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau.” Mere days later, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression began. By this time King had left the NBER for a professorship in economics at New York University.

pages: 366 words: 109,117

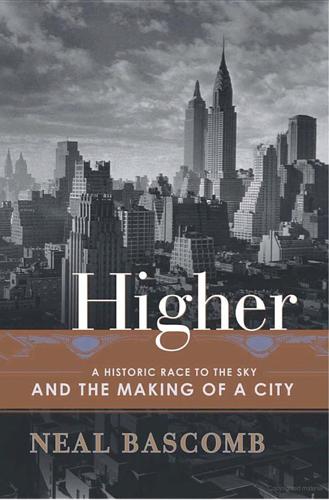

Higher: A Historic Race to the Sky and the Making of a City by Neal Bascomb

buttonwood tree, California gold rush, Charles Lindbergh, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, Ford Model T, hiring and firing, Lewis Mumford, low interest rates, margin call, market bubble, pneumatic tube, Ralph Waldo Emerson, transcontinental railway, Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, W. E. B. Du Bois, Works Progress Administration

Without hesitation, the bulls shrugged off attempts by the Federal Reserve to rein in margin loans. They muzzled the bears who dared predict doom, calling them “destructionists” of America. Investment trusts, like Riordan’s County Trust, opened at a rate of several per week and were leveraged to the hilt. Readers rushed newsstands to read John J. Raskob’s article “Everybody Ought to Be Rich.” One paper called his plan “a practical Utopia”; another said it was the “greatest vision of Wall Street’s greatest mind.” Advice on how to win a fortune on Wall Street became a business in its own right, publishers printing thousands of “morning letters” every day to show how to beat the market.

pages: 497 words: 153,755

The Power of Gold: The History of an Obsession by Peter L. Bernstein

Alan Greenspan, Albert Einstein, Atahualpa, bread and circuses, Bretton Woods, British Empire, business cycle, California gold rush, central bank independence, double entry bookkeeping, Edward Glaeser, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, falling living standards, financial innovation, floating exchange rates, Francisco Pizarro, German hyperinflation, Hernando de Soto, Isaac Newton, joint-stock company, joint-stock limited liability company, Joseph Schumpeter, large denomination, liquidity trap, long peace, low interest rates, Money creation, money: store of value / unit of account / medium of exchange, old-boy network, Paul Samuelson, price stability, profit motive, proprietary trading, random walk, rising living standards, Ronald Reagan, seigniorage, the market place, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, too big to fail, trade route

Then, after going nowhere in the first five months of 1929, it roared upward by 25 percent over the next three months before making its final top in August 1929. In late 1928, when John J. Raskob, Director of General Motors, friend of the DuPonts, and Chairman of the Democratic Committee, wrote in the Ladies' Home Journal that "Everybody Ought to Be Rich," he evidently had plenty of believers.1 It is fair to ask why the unfolding miracles in the stock market were of any concern to the Federal Reserve, which had been established in 1913 to supervise commercial banks and to provide liquidity for the economy as needed. The concern was not misplaced.

pages: 585 words: 151,239

Capitalism in America: A History by Adrian Wooldridge, Alan Greenspan

"Friedman doctrine" OR "shareholder theory", "World Economic Forum" Davos, 2013 Report for America's Infrastructure - American Society of Civil Engineers - 19 March 2013, Affordable Care Act / Obamacare, agricultural Revolution, air freight, Airbnb, airline deregulation, Alan Greenspan, American Society of Civil Engineers: Report Card, Asian financial crisis, bank run, barriers to entry, Bear Stearns, Berlin Wall, Blitzscaling, Bonfire of the Vanities, book value, Bretton Woods, British Empire, business climate, business cycle, business process, California gold rush, Charles Lindbergh, cloud computing, collateralized debt obligation, collective bargaining, Corn Laws, Cornelius Vanderbilt, corporate governance, corporate raider, cotton gin, creative destruction, credit crunch, debt deflation, Deng Xiaoping, disruptive innovation, Donald Trump, driverless car, edge city, Elon Musk, equal pay for equal work, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, Fairchild Semiconductor, Fall of the Berlin Wall, fiat currency, financial deregulation, financial engineering, financial innovation, fixed income, Ford Model T, full employment, general purpose technology, George Gilder, germ theory of disease, Glass-Steagall Act, global supply chain, Great Leap Forward, guns versus butter model, hiring and firing, Ida Tarbell, income per capita, indoor plumbing, informal economy, interchangeable parts, invention of the telegraph, invention of the telephone, Isaac Newton, Jeff Bezos, jimmy wales, John Maynard Keynes: technological unemployment, Joseph Schumpeter, junk bonds, Kenneth Rogoff, Kitchen Debate, knowledge economy, knowledge worker, labor-force participation, land bank, Lewis Mumford, Louis Pasteur, low interest rates, low skilled workers, manufacturing employment, market bubble, Mason jar, mass immigration, McDonald's hot coffee lawsuit, means of production, Menlo Park, Mexican peso crisis / tequila crisis, Michael Milken, military-industrial complex, minimum wage unemployment, mortgage debt, Myron Scholes, Network effects, new economy, New Urbanism, Northern Rock, oil rush, oil shale / tar sands, oil shock, Peter Thiel, Phillips curve, plutocrats, pneumatic tube, popular capitalism, post-industrial society, postindustrial economy, price stability, Productivity paradox, public intellectual, purchasing power parity, Ralph Nader, Ralph Waldo Emerson, RAND corporation, refrigerator car, reserve currency, rising living standards, road to serfdom, Robert Gordon, Robert Solow, Ronald Reagan, Sand Hill Road, savings glut, scientific management, secular stagnation, Silicon Valley, Silicon Valley startup, Simon Kuznets, Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits, South Sea Bubble, sovereign wealth fund, stem cell, Steve Jobs, Steve Wozniak, strikebreaker, supply-chain management, The Great Moderation, The Rise and Fall of American Growth, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, Thorstein Veblen, too big to fail, total factor productivity, trade route, transcontinental railway, tulip mania, Tyler Cowen, Tyler Cowen: Great Stagnation, union organizing, Unsafe at Any Speed, Upton Sinclair, urban sprawl, Vannevar Bush, vertical integration, War on Poverty, washing machines reduced drudgery, Washington Consensus, white flight, wikimedia commons, William Shockley: the traitorous eight, women in the workforce, Works Progress Administration, Yom Kippur War, young professional

New investors could buy on 25 percent margin—that is, borrowing 75 percent of the purchase price. Regular customers could buy on 10 percent margin.1 Some of the wisest people in the country applauded the bull market. In 1927, John Raskob, one of the country’s leading financiers, wrote an article in Ladies’ Home Journal, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich,” advising people of modest means to park their savings in the stock market.2 A year later, Irving Fisher, one of the country’s most respected economists, declared that “stock prices have reached what looks like a permanent high plateau.” Others were more skeptical: as the market took off in 1927, the commerce secretary, Herbert Hoover, condemned the “orgy of mad speculation” on Wall Street and started to explore ways of closing it down.3 The orgy proved more difficult to stop than to start.

pages: 741 words: 179,454

Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk by Satyajit Das

"RICO laws" OR "Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations", "there is no alternative" (TINA), "World Economic Forum" Davos, affirmative action, Alan Greenspan, Albert Einstein, algorithmic trading, Andy Kessler, AOL-Time Warner, Asian financial crisis, asset allocation, asset-backed security, bank run, banking crisis, banks create money, Basel III, Bear Stearns, behavioural economics, Benoit Mandelbrot, Berlin Wall, Bernie Madoff, Big bang: deregulation of the City of London, Black Swan, Bonfire of the Vanities, bonus culture, book value, Bretton Woods, BRICs, British Empire, business cycle, buy the rumour, sell the news, capital asset pricing model, carbon credits, Carl Icahn, Carmen Reinhart, carried interest, Celtic Tiger, clean water, cognitive dissonance, collapse of Lehman Brothers, collateralized debt obligation, corporate governance, corporate raider, creative destruction, credit crunch, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, currency risk, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, deal flow, debt deflation, Deng Xiaoping, deskilling, discrete time, diversification, diversified portfolio, Doomsday Clock, Dr. Strangelove, Dutch auction, Edward Thorp, Emanuel Derman, en.wikipedia.org, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, eurozone crisis, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, Fall of the Berlin Wall, financial engineering, financial independence, financial innovation, financial thriller, fixed income, foreign exchange controls, full employment, Glass-Steagall Act, global reserve currency, Goldman Sachs: Vampire Squid, Goodhart's law, Gordon Gekko, greed is good, Greenspan put, happiness index / gross national happiness, haute cuisine, Herman Kahn, high net worth, Hyman Minsky, index fund, information asymmetry, interest rate swap, invention of the wheel, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, James Carville said: "I would like to be reincarnated as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.", job automation, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, John Bogle, John Meriwether, joint-stock company, Jones Act, Joseph Schumpeter, junk bonds, Kenneth Arrow, Kenneth Rogoff, Kevin Kelly, laissez-faire capitalism, load shedding, locking in a profit, Long Term Capital Management, Louis Bachelier, low interest rates, margin call, market bubble, market fundamentalism, Market Wizards by Jack D. Schwager, Marshall McLuhan, Martin Wolf, mega-rich, merger arbitrage, Michael Milken, Mikhail Gorbachev, Milgram experiment, military-industrial complex, Minsky moment, money market fund, Mont Pelerin Society, moral hazard, mortgage debt, mortgage tax deduction, mutually assured destruction, Myron Scholes, Naomi Klein, National Debt Clock, negative equity, NetJets, Network effects, new economy, Nick Leeson, Nixon shock, Northern Rock, nuclear winter, oil shock, Own Your Own Home, Paul Samuelson, pets.com, Philip Mirowski, Phillips curve, planned obsolescence, plutocrats, Ponzi scheme, price anchoring, price stability, profit maximization, proprietary trading, public intellectual, quantitative easing, quantitative trading / quantitative finance, Ralph Nader, RAND corporation, random walk, Ray Kurzweil, regulatory arbitrage, Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, rent control, rent-seeking, reserve currency, Richard Feynman, Richard Thaler, Right to Buy, risk free rate, risk-adjusted returns, risk/return, road to serfdom, Robert Shiller, Rod Stewart played at Stephen Schwarzman birthday party, rolodex, Ronald Reagan, Ronald Reagan: Tear down this wall, Satyajit Das, savings glut, shareholder value, Sharpe ratio, short selling, short squeeze, Silicon Valley, six sigma, Slavoj Žižek, South Sea Bubble, special economic zone, statistical model, Stephen Hawking, Steve Jobs, stock buybacks, survivorship bias, tail risk, Teledyne, The Chicago School, The Great Moderation, the market place, the medium is the message, The Myth of the Rational Market, The Nature of the Firm, the new new thing, The Predators' Ball, The Theory of the Leisure Class by Thorstein Veblen, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thorstein Veblen, too big to fail, trickle-down economics, Turing test, two and twenty, Upton Sinclair, value at risk, Yogi Berra, zero-coupon bond, zero-sum game

Glassman, an investment columnist for the Washington Post, and Hassett, a former senior economist with the Federal Reserve, inverted normal investment logic by arguing that over the long term shares were no riskier than bonds and that the traditional risk premium (higher return) demanded by investors could be eliminated. The Dow Jones Industrial Average, trading at the time around 11,000, was forecast to more than triple. In a 1929 article “Everybody ought to be rich” in the Ladies’ Home Journal, John Raskob, a director of General Motors, wrote in a similar vein. An investment in shares of just $15 a month would, with dividends reinvested, increase in value to about $80,000 after 20 years. But Raskob, the man who wanted his readers to invest in stock for long-term wealth, was selling his shares even before his article appeared, avoiding the 1929 crash.

pages: 670 words: 194,502

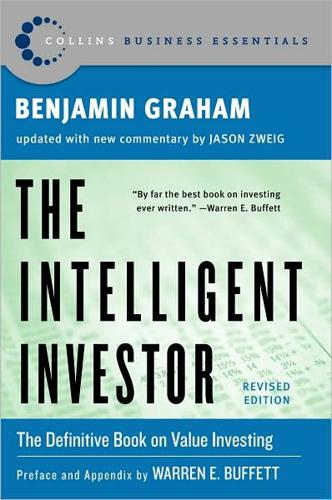

The Intelligent Investor (Collins Business Essentials) by Benjamin Graham, Jason Zweig

3Com Palm IPO, accounting loophole / creative accounting, air freight, Alan Greenspan, Andrei Shleifer, AOL-Time Warner, asset allocation, book value, business cycle, buy and hold, buy low sell high, capital asset pricing model, corporate governance, corporate raider, Daniel Kahneman / Amos Tversky, diversified portfolio, dogs of the Dow, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, George Santayana, hiring and firing, index fund, intangible asset, Isaac Newton, John Bogle, junk bonds, Long Term Capital Management, low interest rates, market bubble, merger arbitrage, Michael Milken, money market fund, new economy, passive investing, price stability, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Richard Thaler, risk tolerance, Robert Shiller, Ronald Reagan, shareholder value, sharing economy, short selling, Silicon Valley, South Sea Bubble, Steve Jobs, stock buybacks, stocks for the long run, survivorship bias, the market place, the rule of 72, transaction costs, tulip mania, VA Linux, Vanguard fund, Y2K, Yogi Berra

It may be well to point up what we have just said by a bit of financial history—especially since there is more than one moral to be drawn from it. In the climactic year 1929 John J. Raskob, a most important figure nationally as well as on Wall Street, extolled the blessings of capitalism in an article in the Ladies’ Home Journal, entitled “Everybody Ought to Be Rich.”* His thesis was that savings of only $15 per month invested in good common stocks—with dividends reinvested—would produce an estate of $80,000 in twenty years against total contributions of only $3,600. If the General Motors tycoon was right, this was indeed a simple road to riches. How nearly right was he?

pages: 1,336 words: 415,037

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life by Alice Schroeder

affirmative action, Alan Greenspan, Albert Einstein, anti-communist, AOL-Time Warner, Ayatollah Khomeini, barriers to entry, Bear Stearns, Black Monday: stock market crash in 1987, Bob Noyce, Bonfire of the Vanities, book value, Brownian motion, capital asset pricing model, card file, centralized clearinghouse, Charles Lindbergh, collateralized debt obligation, computerized trading, Cornelius Vanderbilt, corporate governance, corporate raider, Credit Default Swap, credit default swaps / collateralized debt obligations, desegregation, do what you love, Donald Trump, Eugene Fama: efficient market hypothesis, Everybody Ought to Be Rich, Fairchild Semiconductor, Fillmore Auditorium, San Francisco, financial engineering, Ford Model T, Garrett Hardin, Glass-Steagall Act, global village, Golden Gate Park, Greenspan put, Haight Ashbury, haute cuisine, Honoré de Balzac, If something cannot go on forever, it will stop - Herbert Stein's Law, In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, index fund, indoor plumbing, intangible asset, interest rate swap, invisible hand, Isaac Newton, it's over 9,000, Jeff Bezos, John Bogle, John Meriwether, joint-stock company, joint-stock limited liability company, junk bonds, Larry Ellison, Long Term Capital Management, Louis Bachelier, low interest rates, margin call, market bubble, Marshall McLuhan, medical malpractice, merger arbitrage, Michael Milken, Mikhail Gorbachev, military-industrial complex, money market fund, moral hazard, NetJets, new economy, New Journalism, North Sea oil, paper trading, passive investing, Paul Samuelson, pets.com, Plato's cave, plutocrats, Ponzi scheme, proprietary trading, Ralph Nader, random walk, Ronald Reagan, Salesforce, Scientific racism, shareholder value, short selling, side project, Silicon Valley, Steve Ballmer, Steve Jobs, supply-chain management, telemarketer, The Predators' Ball, The Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, tontine, too big to fail, Tragedy of the Commons, transcontinental railway, two and twenty, Upton Sinclair, War on Poverty, Works Progress Administration, Y2K, yellow journalism, zero-coupon bond

Howard became a deacon in 1928 at the age of 25. 33. Address to the American Society of Newspaper Editors, Washington, D.C., January 25, 1925. Chapter 6 1. Even so, only three in a hundred Americans owned stocks. Many had borrowed heavily to play the market, entranced by John J. Raskob’s article, “Everybody Ought to Be Rich” in the August 1929 Ladies’ Home Journal and Edgar Lawrence Smith’s proof that stocks outperform bonds (Common Stocks as Long-Term Investments. New York: The MacMillan Company, 1925). 2. “Stock Prices Slump $14,000,000,000 in Nation-Wide Stampede to Unload; Bankers to Support Market Today,” New York Times, October 29, 1929; David M.